By Todd Harrison, Venable09.09.21

By now, you may be aware that two pioneering companies, Irwin Naturals and Charlotte’s Web, answered the FDA bell and notified the agency of their intent to market full spectrum hemp extracts (FSHE) with low levels of cannabidiol (CBD). However, while the FDA permitted the filing of the notifications, as required by the law, the agency continued to assert that a product containing CBD is precluded from being marketed as a dietary supplement.

FDA’s position strains credulity at best. Simply stated, FSHE is not excluded from the definition of a dietary supplement because of the following: 1) FSHE is not the same “article” that has been subject to substantial, publicly disclosed clinical investigations as a drug; and 2) FSHE has been marketed as a food and as a dietary supplement prior to any substantial clinical trials investigating cannabis-derived compounds, including CBD isolates. This column discusses whether FSHE is the same article as Epidiolex and/or Sativex.

Making Sense of the Arguments

FDA’s statements that the presence of CBD in FSHE excludes them from dietary ingredient status are without merit. FDA relies heavily on the cultivation and manufacturing process that assures the quality and quantity of CBD as evidence the product is equivalent to Epidiolex and Sativex. FDA arrives at this conclusion based upon the statutory definition of a “dietary supplement” under section 201(ff) of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA).

Specifically, that statutory provision provides in relevant part that “an article” may not be marketed as a dietary supplement, if all of the following are true: 1) it has been authorized for investigation as a new drug; 2) substantial clinical investigations have been instituted on the article and their existence made public; and 3) it was not marketed as a food or dietary supplement prior to being authorized for investigation as a new drug. For purposes of this exclusion, FDA has interpreted “authorized for investigation as a new drug” to mean that an investigational new drug application (IND) has been submitted for the active ingredient or active moiety.

The key issue is whether FSHE is “an article” that has either been approved or investigated as a “drug.” I understand FDA’s position to be that all CBD is the same “article,” which would mean that substantial clinical investigations instituted and made public by GW Pharma several years ago preclude the use of CBD in a dietary supplement—absent evidence establishing that CBD was marketed in dietary supplements prior to GW Pharma’s public announcement of the clinical investigations.

A careful reading of the statute strongly indicates that FDA’s position is contrary to Congressional intent. Congress intended to strike a balance between maintaining the incentive to develop new drugs while allowing access to dietary supplements that may contain a constituent that is the active moiety in the drug, but would not be expected to have the same pharmacological effect. This interpretation is consistent with the Tenth Circuit’s decision in Pharmanex v. Shalala—the seminal case interpreting this provision of section 201(ff) (Pharmanex, Inc. v. Shalala, 221 F.3d 1151 (10th Cir. 2000); 2001 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 4598 (D. Utah Mar. 30, 2001) (district court opinion on remand)).

The Pharmanex case involved a company that developed a proprietary manufacturing process capable of increasing the levels of lovastatin in red yeast rice above the naturally occurring trace levels. FDA took the position that the particular red yeast rice used in Pharmanex’s Cholestin product was precluded under section 201(ff) from being marketed as a dietary ingredient, because it was not present in the food supply prior to FDA’s approval of lovastatin as a drug.

In upholding FDA’s interpretation of section 201(ff), the court noted that Cholestin was pharmacologically equivalent to the lowest-dose lovastatin product marketed by Merck.

In order to fit this paradigm, FDA indicates that a mere 65 mg of CBD is functionally equivalent to Epidiolex, which based on any reasonable calculation requires a minimum of 700 mg of CBD to exert its effect.

This is certainly not the same as the red yeast rice that was the subject of the Pharmanex case; Cholestin contained the same level of lovastatin as the FDA-approved drug. Indeed, the court’s decision was compelled by the fact that, from a pharmacological viewpoint, Pharmanex’s red yeast rice was indistinguishable from Merck’s lovastatin in identity of active ingredient, strength of active ingredient, and mode of action. This is simply not the case with regard to the FSHE ingredients that were the subject of the recent New Dietary Ingredient Notifications (NDINs).

Unique Extracts

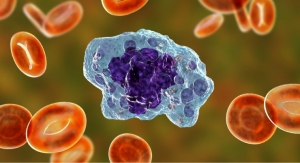

Importantly, studies have shown that multi-component cannabis extracts have displayed differentiated dose-response curves when compared to CBD isolates. Cannabis contains hundreds of compounds and various preclinical studies have shown that different cannabinoids display unique pharmacological and pharmacokinetic profiles.

Furthermore, studies demonstrating the interplay between cannabinoids and other classes of compounds have established the fact that chemical synergy results in unique pharmacological effects. Pharmaceutical drugs consisting of one or two active cannabinoids, at specific standardized amounts, will have distinct mechanisms of action compared to full-spectrum extracts, and each other. FDA simply ignores this fact and does not even attempt to address it.

Indeed, pharmaceutical drugs created from cannabis extracts are an example of how small changes in the ratios of the same cannabinoids can have major consequences in terms of efficacy and pharmacology. For sure, the FSHE in the NDINs had unique chemical profiles when compared to approved drugs. Moreover, the maximum proposed daily amount of CBD from intake of the FSHE differs from that present in Epidiolex. Having established that chemical profile differences translate to changes in pharmacological action, FDA’s position that any level of CBD excludes the ingredient from being eligible as a dietary supplement is misguided.

The primary cannabinoids that define the chemistries of Epidiolex and Sativex are CBD and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which are derived from the acidic precursors cannabidiolic acid (CBDA) and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA).

However, Cannabis sativa contains approximately 120 different cannabinoids, which have been described in peer-reviewed journal articles. Cannabinoids are unique to the Cannabis sativa plant and can be separated into two types, neutral cannabinoids and acidic cannabinoids, depending on whether they contain a carboxyl group.

In live plants, cannabinoids are found in their acidic form. The decarboxylation reaction occurs through non-enzymatic processes, such as light exposure, heating, or aging. After the plant is harvested, each processing step—such as drying, milling, storage, extraction, and/or smoking—produces a little more of the neutral, decarboxylated cannabinoids.

Fundamental Differences

Simply stated, FSHE is fundamentally different from both Epidiolex and Sativex. Multicomponent hemp extract with trace levels of naturally occurring THC (< 0.3%) and other naturally occurring cannabinoids, terpenoids, flavonoids, and phytochemicals, has not been approved in any new drug. FSHE is further distinguished by:

In the parlance of the Pharmanex opinion, the relationship between FSHE and Epidiolex and Sativex is a far cry from the nearly identical properties shared by Cholestin and prescription lovastatin products. FSHE exhibits differentiated pharmacological properties and is not the same “article” that is the subject of substantial clinical investigations or FDA approval for Dravet syndrome or Lennox-Gastaut syndrome—two rare forms of epilepsy.

To state it more concisely, FSHE and GW Pharma’s cannabis-derived drugs have nothing in common with each other. The NDIN exercise Irwin Naturals and Charlotte’s Web completed shows that FDA is unlikely to change its mind absent action by Congress to amend the law to make it clear that FSHE is not precluded under the FDCA.

About the Author: Todd Harrison is partner with Venable, which is located in Washington, D.C. He advises food and drug companies on a variety of FDA and FTC matters, with an emphasis on dietary supplement, functional food, biotech, legislative, adulteration, labeling and advertising issues. He can be reached at 575 7th St. NW, Washington, D.C. 20004, Tel: 202-344-4724; E-mail: taharrison@venable.com.

FDA’s position strains credulity at best. Simply stated, FSHE is not excluded from the definition of a dietary supplement because of the following: 1) FSHE is not the same “article” that has been subject to substantial, publicly disclosed clinical investigations as a drug; and 2) FSHE has been marketed as a food and as a dietary supplement prior to any substantial clinical trials investigating cannabis-derived compounds, including CBD isolates. This column discusses whether FSHE is the same article as Epidiolex and/or Sativex.

Making Sense of the Arguments

FDA’s statements that the presence of CBD in FSHE excludes them from dietary ingredient status are without merit. FDA relies heavily on the cultivation and manufacturing process that assures the quality and quantity of CBD as evidence the product is equivalent to Epidiolex and Sativex. FDA arrives at this conclusion based upon the statutory definition of a “dietary supplement” under section 201(ff) of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA).

Specifically, that statutory provision provides in relevant part that “an article” may not be marketed as a dietary supplement, if all of the following are true: 1) it has been authorized for investigation as a new drug; 2) substantial clinical investigations have been instituted on the article and their existence made public; and 3) it was not marketed as a food or dietary supplement prior to being authorized for investigation as a new drug. For purposes of this exclusion, FDA has interpreted “authorized for investigation as a new drug” to mean that an investigational new drug application (IND) has been submitted for the active ingredient or active moiety.

The key issue is whether FSHE is “an article” that has either been approved or investigated as a “drug.” I understand FDA’s position to be that all CBD is the same “article,” which would mean that substantial clinical investigations instituted and made public by GW Pharma several years ago preclude the use of CBD in a dietary supplement—absent evidence establishing that CBD was marketed in dietary supplements prior to GW Pharma’s public announcement of the clinical investigations.

A careful reading of the statute strongly indicates that FDA’s position is contrary to Congressional intent. Congress intended to strike a balance between maintaining the incentive to develop new drugs while allowing access to dietary supplements that may contain a constituent that is the active moiety in the drug, but would not be expected to have the same pharmacological effect. This interpretation is consistent with the Tenth Circuit’s decision in Pharmanex v. Shalala—the seminal case interpreting this provision of section 201(ff) (Pharmanex, Inc. v. Shalala, 221 F.3d 1151 (10th Cir. 2000); 2001 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 4598 (D. Utah Mar. 30, 2001) (district court opinion on remand)).

The Pharmanex case involved a company that developed a proprietary manufacturing process capable of increasing the levels of lovastatin in red yeast rice above the naturally occurring trace levels. FDA took the position that the particular red yeast rice used in Pharmanex’s Cholestin product was precluded under section 201(ff) from being marketed as a dietary ingredient, because it was not present in the food supply prior to FDA’s approval of lovastatin as a drug.

In upholding FDA’s interpretation of section 201(ff), the court noted that Cholestin was pharmacologically equivalent to the lowest-dose lovastatin product marketed by Merck.

In order to fit this paradigm, FDA indicates that a mere 65 mg of CBD is functionally equivalent to Epidiolex, which based on any reasonable calculation requires a minimum of 700 mg of CBD to exert its effect.

This is certainly not the same as the red yeast rice that was the subject of the Pharmanex case; Cholestin contained the same level of lovastatin as the FDA-approved drug. Indeed, the court’s decision was compelled by the fact that, from a pharmacological viewpoint, Pharmanex’s red yeast rice was indistinguishable from Merck’s lovastatin in identity of active ingredient, strength of active ingredient, and mode of action. This is simply not the case with regard to the FSHE ingredients that were the subject of the recent New Dietary Ingredient Notifications (NDINs).

Unique Extracts

Importantly, studies have shown that multi-component cannabis extracts have displayed differentiated dose-response curves when compared to CBD isolates. Cannabis contains hundreds of compounds and various preclinical studies have shown that different cannabinoids display unique pharmacological and pharmacokinetic profiles.

Furthermore, studies demonstrating the interplay between cannabinoids and other classes of compounds have established the fact that chemical synergy results in unique pharmacological effects. Pharmaceutical drugs consisting of one or two active cannabinoids, at specific standardized amounts, will have distinct mechanisms of action compared to full-spectrum extracts, and each other. FDA simply ignores this fact and does not even attempt to address it.

Indeed, pharmaceutical drugs created from cannabis extracts are an example of how small changes in the ratios of the same cannabinoids can have major consequences in terms of efficacy and pharmacology. For sure, the FSHE in the NDINs had unique chemical profiles when compared to approved drugs. Moreover, the maximum proposed daily amount of CBD from intake of the FSHE differs from that present in Epidiolex. Having established that chemical profile differences translate to changes in pharmacological action, FDA’s position that any level of CBD excludes the ingredient from being eligible as a dietary supplement is misguided.

The primary cannabinoids that define the chemistries of Epidiolex and Sativex are CBD and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which are derived from the acidic precursors cannabidiolic acid (CBDA) and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA).

However, Cannabis sativa contains approximately 120 different cannabinoids, which have been described in peer-reviewed journal articles. Cannabinoids are unique to the Cannabis sativa plant and can be separated into two types, neutral cannabinoids and acidic cannabinoids, depending on whether they contain a carboxyl group.

In live plants, cannabinoids are found in their acidic form. The decarboxylation reaction occurs through non-enzymatic processes, such as light exposure, heating, or aging. After the plant is harvested, each processing step—such as drying, milling, storage, extraction, and/or smoking—produces a little more of the neutral, decarboxylated cannabinoids.

Fundamental Differences

Simply stated, FSHE is fundamentally different from both Epidiolex and Sativex. Multicomponent hemp extract with trace levels of naturally occurring THC (< 0.3%) and other naturally occurring cannabinoids, terpenoids, flavonoids, and phytochemicals, has not been approved in any new drug. FSHE is further distinguished by:

- FSHE contains CBD and trace amounts of THC as a component of a more complex mixture that has not itself been approved as a drug.

- FSHE does not contain added CBD or THC.

- FSHE is being marketed for use at a dose level that would not expose consumers to the therapeutic levels of CBD or THC used in approved drugs.

In the parlance of the Pharmanex opinion, the relationship between FSHE and Epidiolex and Sativex is a far cry from the nearly identical properties shared by Cholestin and prescription lovastatin products. FSHE exhibits differentiated pharmacological properties and is not the same “article” that is the subject of substantial clinical investigations or FDA approval for Dravet syndrome or Lennox-Gastaut syndrome—two rare forms of epilepsy.

To state it more concisely, FSHE and GW Pharma’s cannabis-derived drugs have nothing in common with each other. The NDIN exercise Irwin Naturals and Charlotte’s Web completed shows that FDA is unlikely to change its mind absent action by Congress to amend the law to make it clear that FSHE is not precluded under the FDCA.