By Todd Harrison and Richard A. Starr, Venable11.07.22

FDA issued a proposed rule on Sep. 28, 2022 that updates the definition of the term “healthy” when used on FDA-regulated products. Comments are due Dec. 28, 2022.

In short, the rule would require any food making a claim that it is “healthy,” to contain a certain amount of a certain food group—such as fruits, dairy, or proteins—and not have too much saturated fat, sodium, or added sugars.

As a result, some vegetables and meat that could not previously make “healthy” claims now could do so, but the proposed limitations remain strict overall, and potentially close off the pathway for some food manufacturers to reasonably make such claims in the future.

Significantly, FDA’s proposal would broaden the circumstances under which a claim could be considered an implied “healthy” claim. FDA’s proposal signals that it believes “healthy” claims could be implied more broadly in that “any information on the label or labeling that puts the term “healthy” into a nutritional context would make “healthy” an implied nutrient content claim when it is used to characterize the food.

This notion includes the word “healthy” when used in a brand name and another nutrient content claim such as “low sodium” is used elsewhere on the product. Plus, whether a “healthy” claim is implied would no longer require that the accompanying material be a “claim or statement about a nutrient,” but only that it be “information about the nutrition content of the food.”

For example, FDA states: “if the label on a food product characterizes food using the term ‘healthy’ and elsewhere stated that the product is ‘made with whole grain ingredients,’ or ‘made with real fruits and vegetables,’ or ‘contains a variety of nuts,’ this would put ‘healthy’ in a nutritional context because the labeling implies that the food should contain nutrients commonly associated with and contributed by those food components.”

Since 1994, when the definition originally came about, however, nutrition and health science evolved to focus more on whole foods and dietary patterns than on the intake of specific nutrients. KIND LLC pointed this out in a Citizen Petition response to a Warning Letter the company received from FDA in 2015, citing the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. As a likely result of mounting pressure from the changing nutrition science, the Citizen Petition, and elsewhere, FDA decided in the fall of 2016 that it would start the process of redefining what constitutes “healthy” for nutrient content claims.

FDA simultaneously issued guidance that it would in the meantime exercise enforcement discretion “for foods that have a fat profile of predominantly monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, but do not meet the regulatory definition of ‘low fat,’ and on foods that contain at least 10 percent of the DV per reference amount customarily consumed (RACC) of potassium or vitamin D.” Since that time, FDA has been taking public comments under Docket No. FDA-2016-D-2335 regarding the use of the term “healthy.” The agency held a public meeting on the subject as well.

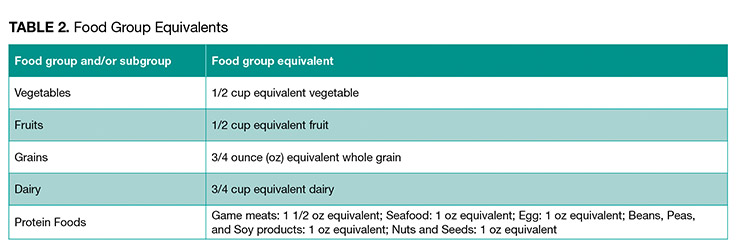

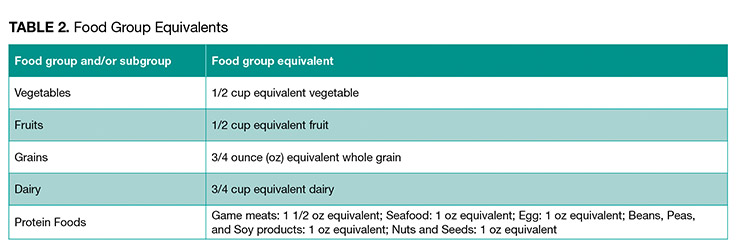

Ultimately, foods would be required to “contain a certain amount of food (a ‘food group equivalent’ (FGE)) from at least one of these recommended food groups or subgroups (e.g., 1/2 cup of fruit or 3/4 cup of dairy) to be labeled ‘healthy.’”

Based on these proposed criteria, you may have some common questions.

For example, grain products are considered an individual food product. FDA proposes to require that for an individual grain product to bear a “healthy” claim, that product would need to contain at least 3/4 oz equivalent of whole grain, and also would be limited to the baseline nutrient limitations: added sugars content must be no greater than 5% DV per RACC, the sodium content must be no greater than 10% DV per RACC, and the saturated fat content must be no greater than 5% DV per RACC.

Indeed, oil-based spreads, such as margarine, could bear the “healthy” claim “only when their fat content comes solely from oils and where the product’s overall saturated fat content is no more than 20 percent of total fat.” In addition, added sugars could not exceed 0% DV, and there is a sodium limit of 5% DV.

Finally, “plant-based milk alternatives and plant-based yogurt alternatives whose overall nutritional content is similar to dairy (e.g., provide similar amounts of protein, calcium, potassium, magnesium, vitamin D, and vitamin A)” could potentially qualify for a “healthy” claim.

However, the expansion of what may be considered an implied claim, and the marked shift in agency priorities from a nutrient-based evaluation to that of dietary patterns and food groups could affect how manufacturers decide to design and market their current food product lines in the short term.

At the same time, creating a rule that has little practical utility, and is based on a dated mode of what is “appropriate” dietary guidance, leaves one wondering why FDA believes it has the power to define “healthy.” Ultimately, while the rule claims to take into consideration the government’s own evolving understanding of nutrition—which historically it has not done a very good job in getting right—it will likely add to misunderstanding about proper diet and nutrition.

Intrinsically, we know fruits and vegetables are good for us, but many would question whether many grains really are, for example.

FDA has once again promulgated a rule that makes little sense, includes many exceptions, and is simultaneously both too narrow and too broad. This is likely to lead to more plaintiff class action lawsuits as marketing companies attempt to bend the rules while other products that are indeed “healthy” would not be considered as such under this rule.

It is time we push back on this type of regulation because when it comes to nutrition the government doesn’t get it right. I appreciate the agency is trying to do the right thing, but sometimes the right thing is to do nothing. It would be more meaningful to rescind some misinformed nutrient content claims, like “low-fat,” which effectively stripped fat from peoples’ diets, increased simple carbs, and led to rising rates of obesity and type 2 diabetes.

We encourage any stakeholders to consider filing comments by the Dec. 28, 2022 deadline after reviewing the proposal in greater detail with counsel.

About the Author: Todd Harrison is partner with Venable, which is located in Washington, D.C. He advises food and drug companies on a variety of FDA and FTC matters, with an emphasis on dietary supplement, functional food, biotech, legislative, adulteration, labeling and advertising issues. He can be reached at 575 7th St. NW, Washington, D.C. 20004, Tel: 202-344-4724; E-mail: taharrison@venable.com.

Richard Starr, is an associate at Venable, who advises clients on Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Federal Trade Commission (FTC) matters, including the labeling, advertising, and marketing of cosmetics, dietary supplements, and foods. He can be reached at RAStarr@Venable.com.

In short, the rule would require any food making a claim that it is “healthy,” to contain a certain amount of a certain food group—such as fruits, dairy, or proteins—and not have too much saturated fat, sodium, or added sugars.

As a result, some vegetables and meat that could not previously make “healthy” claims now could do so, but the proposed limitations remain strict overall, and potentially close off the pathway for some food manufacturers to reasonably make such claims in the future.

Significantly, FDA’s proposal would broaden the circumstances under which a claim could be considered an implied “healthy” claim. FDA’s proposal signals that it believes “healthy” claims could be implied more broadly in that “any information on the label or labeling that puts the term “healthy” into a nutritional context would make “healthy” an implied nutrient content claim when it is used to characterize the food.

This notion includes the word “healthy” when used in a brand name and another nutrient content claim such as “low sodium” is used elsewhere on the product. Plus, whether a “healthy” claim is implied would no longer require that the accompanying material be a “claim or statement about a nutrient,” but only that it be “information about the nutrition content of the food.”

For example, FDA states: “if the label on a food product characterizes food using the term ‘healthy’ and elsewhere stated that the product is ‘made with whole grain ingredients,’ or ‘made with real fruits and vegetables,’ or ‘contains a variety of nuts,’ this would put ‘healthy’ in a nutritional context because the labeling implies that the food should contain nutrients commonly associated with and contributed by those food components.”

Background

Historically, when claiming a product is “healthy,” advertisers have needed to show that the product meets certain minimum nutrition standards, such as a range of acceptable total or saturated fat, cholesterol, or sodium, or certain vitamins and minerals. These requirements reflected an emphasis on whether consumers are ingesting the right levels of nutrients. This meant some foods that might not have actual whole food ingredients, but met the nutrient requirements as a result of, perhaps, vitamin and mineral fortification, could potentially make “healthy” claims.Since 1994, when the definition originally came about, however, nutrition and health science evolved to focus more on whole foods and dietary patterns than on the intake of specific nutrients. KIND LLC pointed this out in a Citizen Petition response to a Warning Letter the company received from FDA in 2015, citing the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. As a likely result of mounting pressure from the changing nutrition science, the Citizen Petition, and elsewhere, FDA decided in the fall of 2016 that it would start the process of redefining what constitutes “healthy” for nutrient content claims.

FDA simultaneously issued guidance that it would in the meantime exercise enforcement discretion “for foods that have a fat profile of predominantly monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, but do not meet the regulatory definition of ‘low fat,’ and on foods that contain at least 10 percent of the DV per reference amount customarily consumed (RACC) of potassium or vitamin D.” Since that time, FDA has been taking public comments under Docket No. FDA-2016-D-2335 regarding the use of the term “healthy.” The agency held a public meeting on the subject as well.

A New Landscape and Common Questions

FDA’s new proposed rule would change the landscape of “healthy” claims in several ways. Indeed, the agency’s overall approach is notable in that the rule no longer focuses solely on individual nutrients. Instead, FDA only believes “healthy” claims should appear on products in a manner consistent with the current nutrition science espoused in the Dietary Guidelines 2020-2025, particularly regarding healthy dietary patterns and the consumption of certain food groups.Ultimately, foods would be required to “contain a certain amount of food (a ‘food group equivalent’ (FGE)) from at least one of these recommended food groups or subgroups (e.g., 1/2 cup of fruit or 3/4 cup of dairy) to be labeled ‘healthy.’”

Based on these proposed criteria, you may have some common questions.

1. Are any foods automatically allowed to use the claim “healthy”?

Select categories of food may automatically use the “healthy” claim because of their nutrient content and positive contribution to an overall healthy diet. However, the impact of this newfound ability to make this claim is unclear, as many consumers likely already believe items like salmon and raw vegetables are “healthy.”2. The current healthy claim requires strict nutrient limitations. Are any of those limitations still in effect?

Nutrient limitations still exist with respect to sodium, added sugars, and saturated fat. There is a baseline level established, but depending on the food category, the baseline may be adjusted based on specific nutrient considerations regarding the food group. For example, the baseline 5% DV limit for saturated fat jumps to 10% of the DV for dairy products, game meats, seafood, and eggs, while that baseline leaps to 20% of total fat for oils and oil-based spreads and dressings.- Sodium is limited more strictly. The previous limit was 480 mg and now is 230 mg per RACC (10% DV).

- Added sugars are limited to a baseline level of ≤5% of the DV per RACC (≤2 1/2 g for adults and children 4 years of age and older).

- Saturated fat is limited to a baseline level of ≤1 g for adults and children 4 years of age and older, which is 5% DV per RACC.

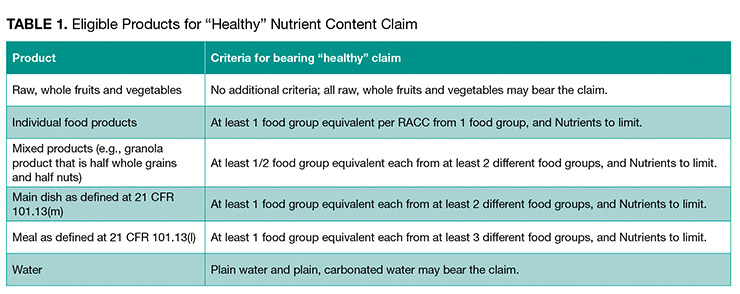

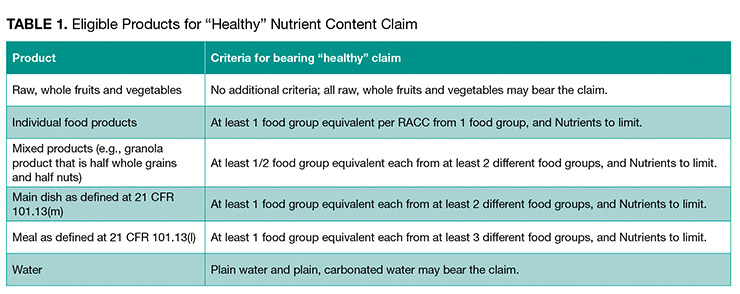

3. What kinds of food are eligible to bear a “healthy” claim?

Foods that can bear the claim “healthy” are broken into several categories. The category and corresponding criteria are summarized in Table 1 (provided in the proposed rule).

4. What is a “food group equivalent,” exactly, and how does it affect the claim I want to make?

To enable these criteria, FDA has also established “food group equivalents” (FGE) (Table 2). As mentioned, an FGE is the amount of a food or food subgroup that must be contained in a product in order to be labeled “healthy.”For example, grain products are considered an individual food product. FDA proposes to require that for an individual grain product to bear a “healthy” claim, that product would need to contain at least 3/4 oz equivalent of whole grain, and also would be limited to the baseline nutrient limitations: added sugars content must be no greater than 5% DV per RACC, the sodium content must be no greater than 10% DV per RACC, and the saturated fat content must be no greater than 5% DV per RACC.

5. What other changes have been made that could affect competitors in food categories?

It is noteworthy that FDA has determined that certain food products may belong in a food group or subgroup for purposes of qualifying for a “healthy” claim. For example, although oils are not a food group, FDA proposes to include 100% oils, oil-based spreads, and oil-based dressings in the definition of “healthy” where they meet certain specified requirements.Indeed, oil-based spreads, such as margarine, could bear the “healthy” claim “only when their fat content comes solely from oils and where the product’s overall saturated fat content is no more than 20 percent of total fat.” In addition, added sugars could not exceed 0% DV, and there is a sodium limit of 5% DV.

Finally, “plant-based milk alternatives and plant-based yogurt alternatives whose overall nutritional content is similar to dairy (e.g., provide similar amounts of protein, calcium, potassium, magnesium, vitamin D, and vitamin A)” could potentially qualify for a “healthy” claim.

6. What is the significance of these changes and how do I comment on the proposed rule?

In all, the proposals from FDA could very well change the claims that consumers see in supermarkets in the years to come. With a great deal of time ahead of us before these changes take place, given the slow plodding of agency rulemaking, we are not likely to see the on-label results of these formal claims on a broad scale for some time.However, the expansion of what may be considered an implied claim, and the marked shift in agency priorities from a nutrient-based evaluation to that of dietary patterns and food groups could affect how manufacturers decide to design and market their current food product lines in the short term.

At the same time, creating a rule that has little practical utility, and is based on a dated mode of what is “appropriate” dietary guidance, leaves one wondering why FDA believes it has the power to define “healthy.” Ultimately, while the rule claims to take into consideration the government’s own evolving understanding of nutrition—which historically it has not done a very good job in getting right—it will likely add to misunderstanding about proper diet and nutrition.

Intrinsically, we know fruits and vegetables are good for us, but many would question whether many grains really are, for example.

FDA has once again promulgated a rule that makes little sense, includes many exceptions, and is simultaneously both too narrow and too broad. This is likely to lead to more plaintiff class action lawsuits as marketing companies attempt to bend the rules while other products that are indeed “healthy” would not be considered as such under this rule.

It is time we push back on this type of regulation because when it comes to nutrition the government doesn’t get it right. I appreciate the agency is trying to do the right thing, but sometimes the right thing is to do nothing. It would be more meaningful to rescind some misinformed nutrient content claims, like “low-fat,” which effectively stripped fat from peoples’ diets, increased simple carbs, and led to rising rates of obesity and type 2 diabetes.

We encourage any stakeholders to consider filing comments by the Dec. 28, 2022 deadline after reviewing the proposal in greater detail with counsel.

About the Author: Todd Harrison is partner with Venable, which is located in Washington, D.C. He advises food and drug companies on a variety of FDA and FTC matters, with an emphasis on dietary supplement, functional food, biotech, legislative, adulteration, labeling and advertising issues. He can be reached at 575 7th St. NW, Washington, D.C. 20004, Tel: 202-344-4724; E-mail: taharrison@venable.com.

Richard Starr, is an associate at Venable, who advises clients on Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Federal Trade Commission (FTC) matters, including the labeling, advertising, and marketing of cosmetics, dietary supplements, and foods. He can be reached at RAStarr@Venable.com.