By Dilip Ghosh, PhD, FACN, nutriConnect10.07.19

Cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum; C. zeylanicum) is a small evergreen tree, 10-15 meters tall, belonging to the family Lauraceae, native to Sri Lanka and South India. The flowers, which are arranged in panicles, have a greenish color and have a distinct odor. The fruit is a purple one-centimeter berry containing a single seed. Its flavor is due to an aromatic essential oil which makes up 0.5-1% of its composition.

Cinnamomum verum (also known as Cinnamomum zeylanicum [CZ] or Ceylon cinnamon,) and Cinnamomum cassia (also known as Cassia cinnamon [CC] or Chinese cinnamon) are the most popular species in the world. Nevertheless, the genus Cinnamomum actually consists of approximately 250 species with distinctive genotypes and phenotypes.

These plants are economically important due to their broad uses in the food and pharmaceutical industries. The aroma and essence industries are the major users of cinnamon due to its fragrance, but this can be incorporated into different varieties of food products and also as functional food ingredients in vitamins, minerals, probiotics, phytosterols, and antioxidants. Cinnamon has been explored for medicinal use in the last decade; this article will discuss its journey in different health domains.

Chemistry

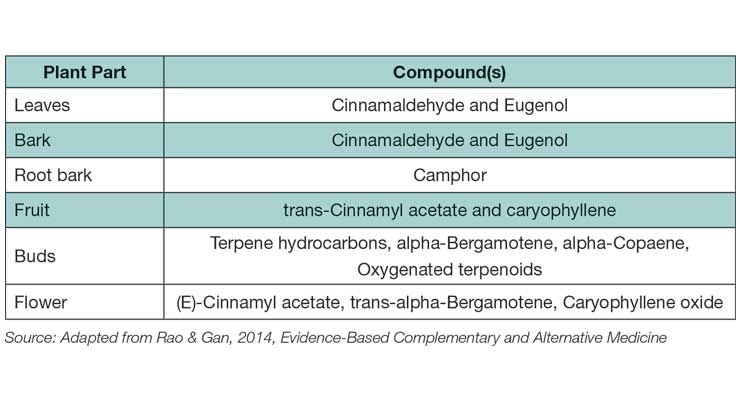

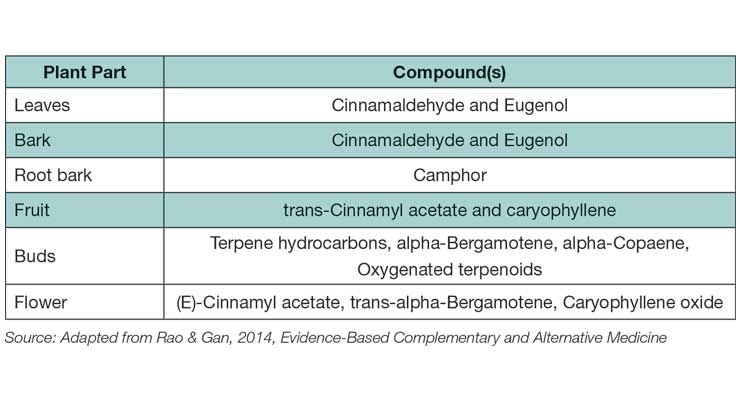

Cinnamon consists of a variety of resinous compounds, including cinnamaldehyde, cinnamate, cinnamic acid, and numerous essential oils (Table 1). The spicy taste and fragrance are due to the presence of oxidized cinnamaldehyde. As cinnamon ages, it darkens in color, improving the resinous compounds. The presence of a wide range of essential oils, such as trans-cinnamaldehyde, cinnamyl acetate, eugenol, L-borneol, caryophyllene oxide, b-caryophyllene, L-bornyl acetate, E-nerolidol, ɑ-cubebene, ɑ-terpineol, terpinolene, and ɑ-thujene, has been reported.

One important difference between CC and CZ is their coumarin (1,2-benzopyrone) content. The levels of coumarins in CC appear to be very high and sometimes impose health risks if consumed regularly in higher quantities (The German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment).

Traditional Use of Cinnamon

In addition to being used as a spice and flavoring agent, cinnamon is also added to chewing gums due to its mouth refreshing effects and ability to decrease bad breath. Cinnamon is also used as tooth powder and to treat toothaches, dental problems, oral microbiota, and bad breath due to its wide range of anti-microbial properties. Cinnamon is a coagulant and prevents bleeding. Cinnamon also increases blood circulation in the uterus and advances tissue regeneration. In native Ayurvedic medicine, cinnamon is considered a remedy for respiratory, digestive, and gynaecological ailments.

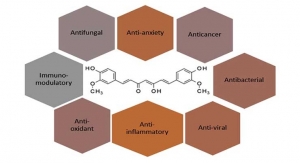

Modern Medicinal Use

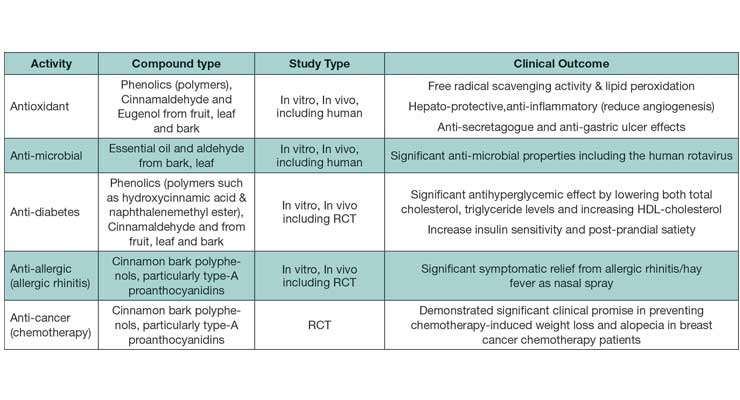

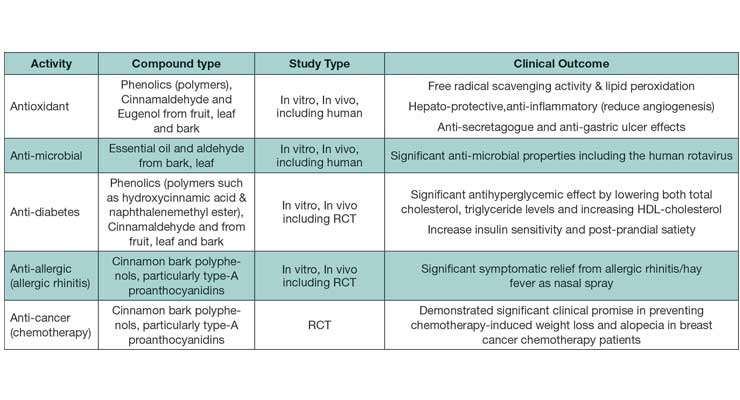

The health benefits of cinnamon in clinical situations have been explored over the last decade. Numerous in vitro and in vivo studies in animals and humans have demonstrated an array of beneficial health effects, such as anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, reducing cardiovascular disorders, boosting cognitive function, and reducing risk of colonic cancer. But there are still a lack of well-designed, randomized, placebo-controlled trials (RCTs) to substantiate these in vitro and animal results. A few recent well-designed RCTs in allergic rhinitis and chemotherapy-induced weight loss and alopecia strengthened understanding of the medicinal properties of cinnamon. Table 2 describes various physiochemical properties and clinical outcomes.

Conclusion & Way Forward

Conclusion & Way Forward

Cinnamon bark research has moved many miles ahead from culinary use as a spice and traditional medicinal use. Several of its medicinal properties and safety are now validated through modern scientific methods. These include anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory, cardioprotective, and neurological disorders.

Cinnamon bark extract already showed strong clinical evidence in the treatment of diabetes mellitus for sugar control and prevention of complications. The primary driving force for the potential of cinnamon bark for immune system benefits is polyphenols, especially proanthocyanidins. The true multifaceted clinical potential of cinnamon polyphenols has surfaced only recently with clinical evidence for immune/allergic inflammatory conditions such as allergic rhinitis and chemotherapy side effects. The ability of cinnamon polyphenols to protect the immune system is now being explored for various prophylactic applications/uses against chronic allergic rhinitis conditions, viral infections, and side effects of chemotherapy to improve quality of life.

References

Dilip Ghosh, PhD, FACN

nutriConnect

About the author: Dilip Ghosh, PhD, FACN, is director of nutriConnect, based in Sydney, Australia. He is also professionally involved with NICM, Western Sydney University, Australia, and is an Honorary Ambassador with the Global Harmonization Initiative (GHI). Dr. Ghosh received his PhD in biomedical science from University of Calcutta, India. He has been involved in drug development (both synthetic and natural) and functional food research and development both in academic and industry domains. Dr. Ghosh has published more than 90 papers in peer-reviewed journals, and he has authored many books, including: “Biotechnology in Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals,” “Innovation in Healthy and Functional Foods,” “Clinical Perspective of Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals,” and “Pharmaceuticals to Nutraceuticals: A Shift in Disease Prevention” under CRC Press. He can be reached at dghosh@optusnet.com.au; www.nutriconnect.com.au.

Cinnamomum verum (also known as Cinnamomum zeylanicum [CZ] or Ceylon cinnamon,) and Cinnamomum cassia (also known as Cassia cinnamon [CC] or Chinese cinnamon) are the most popular species in the world. Nevertheless, the genus Cinnamomum actually consists of approximately 250 species with distinctive genotypes and phenotypes.

These plants are economically important due to their broad uses in the food and pharmaceutical industries. The aroma and essence industries are the major users of cinnamon due to its fragrance, but this can be incorporated into different varieties of food products and also as functional food ingredients in vitamins, minerals, probiotics, phytosterols, and antioxidants. Cinnamon has been explored for medicinal use in the last decade; this article will discuss its journey in different health domains.

Chemistry

Cinnamon consists of a variety of resinous compounds, including cinnamaldehyde, cinnamate, cinnamic acid, and numerous essential oils (Table 1). The spicy taste and fragrance are due to the presence of oxidized cinnamaldehyde. As cinnamon ages, it darkens in color, improving the resinous compounds. The presence of a wide range of essential oils, such as trans-cinnamaldehyde, cinnamyl acetate, eugenol, L-borneol, caryophyllene oxide, b-caryophyllene, L-bornyl acetate, E-nerolidol, ɑ-cubebene, ɑ-terpineol, terpinolene, and ɑ-thujene, has been reported.

One important difference between CC and CZ is their coumarin (1,2-benzopyrone) content. The levels of coumarins in CC appear to be very high and sometimes impose health risks if consumed regularly in higher quantities (The German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment).

Traditional Use of Cinnamon

In addition to being used as a spice and flavoring agent, cinnamon is also added to chewing gums due to its mouth refreshing effects and ability to decrease bad breath. Cinnamon is also used as tooth powder and to treat toothaches, dental problems, oral microbiota, and bad breath due to its wide range of anti-microbial properties. Cinnamon is a coagulant and prevents bleeding. Cinnamon also increases blood circulation in the uterus and advances tissue regeneration. In native Ayurvedic medicine, cinnamon is considered a remedy for respiratory, digestive, and gynaecological ailments.

Modern Medicinal Use

The health benefits of cinnamon in clinical situations have been explored over the last decade. Numerous in vitro and in vivo studies in animals and humans have demonstrated an array of beneficial health effects, such as anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, reducing cardiovascular disorders, boosting cognitive function, and reducing risk of colonic cancer. But there are still a lack of well-designed, randomized, placebo-controlled trials (RCTs) to substantiate these in vitro and animal results. A few recent well-designed RCTs in allergic rhinitis and chemotherapy-induced weight loss and alopecia strengthened understanding of the medicinal properties of cinnamon. Table 2 describes various physiochemical properties and clinical outcomes.

Cinnamon bark research has moved many miles ahead from culinary use as a spice and traditional medicinal use. Several of its medicinal properties and safety are now validated through modern scientific methods. These include anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory, cardioprotective, and neurological disorders.

Cinnamon bark extract already showed strong clinical evidence in the treatment of diabetes mellitus for sugar control and prevention of complications. The primary driving force for the potential of cinnamon bark for immune system benefits is polyphenols, especially proanthocyanidins. The true multifaceted clinical potential of cinnamon polyphenols has surfaced only recently with clinical evidence for immune/allergic inflammatory conditions such as allergic rhinitis and chemotherapy side effects. The ability of cinnamon polyphenols to protect the immune system is now being explored for various prophylactic applications/uses against chronic allergic rhinitis conditions, viral infections, and side effects of chemotherapy to improve quality of life.

References

- Jakhetia V et al. 2010. Cinnamon: A Pharmacological Review. J Adv Sci Res, 1(2); 19-23.

- Mehta A et al. 2019. Efficacy and safety of standardized Cinnamon bark extract for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced weight loss and alopecia in patients with breast cancer” A randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled study. Asian J Pharm Clin Res, 12 (10): 1-6 (In press).

- Rao PV and Gan SH. 2014, Cinnamon: A Multifaceted Medicinal Plant. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med, Article ID 642942, 12 pages.

- Ranasinghe P et al. 2013. Medicinal properties of ‘true’ cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum): a systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med, 13:275

- Walanj S et al. 2014.Efficacy and safety of the topical use of intranasal cinnamon bark extract in seasonal allergic rhinitis patients: A double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study.

- J Herbal Med, 4: 37-47.

Dilip Ghosh, PhD, FACN

nutriConnect

About the author: Dilip Ghosh, PhD, FACN, is director of nutriConnect, based in Sydney, Australia. He is also professionally involved with NICM, Western Sydney University, Australia, and is an Honorary Ambassador with the Global Harmonization Initiative (GHI). Dr. Ghosh received his PhD in biomedical science from University of Calcutta, India. He has been involved in drug development (both synthetic and natural) and functional food research and development both in academic and industry domains. Dr. Ghosh has published more than 90 papers in peer-reviewed journals, and he has authored many books, including: “Biotechnology in Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals,” “Innovation in Healthy and Functional Foods,” “Clinical Perspective of Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals,” and “Pharmaceuticals to Nutraceuticals: A Shift in Disease Prevention” under CRC Press. He can be reached at dghosh@optusnet.com.au; www.nutriconnect.com.au.