By Dilip Ghosh, PhD, FACN, nutriConnect07.05.17

Age-associated cognitive decline (AACD), which is also known as non-pathological cognitive aging—is an important human experience which differs in extent between individuals and also between different stages in the life cycle. Cognitive decline is among the most feared aspects of growing old. In terms of the financial, personal, and societal burdens, AACD is considered a most costly affair. The determinants of the differences in age-related cognitive decline are not fully understood. As people age, they change in a myriad of ways—both biological and psychological, some of these changes may be for the better, and others are not.

Brain in Old Age

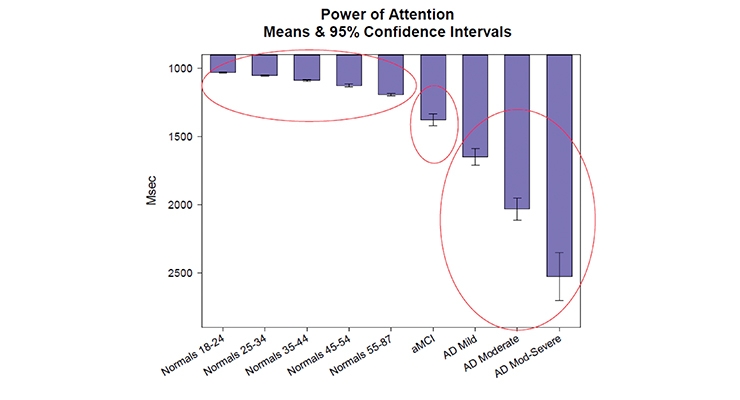

The brain undergoes tremendous age-associated structural and functional changes with age. Figure 1 describes the transition of cognitive decline from normal aging to Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s disease.

A range of cognitive decline in normal aging starts in the 20s; these declines are stable at the age of 75. The most obvious is a steady decrease in brain size, an increase in ventricular spaces, and cerebrospinal fluid. The most severe effects occur in prefrontal regions, but general brain atrophy accelerates in old age via anterior-posterior gradient. Brain white matter volume is not affected that much until about age 70. Also, cerebral dopamine receptor density depletes with age, which plays a central role in regulating attention and in modulating response to contextual stimuli.

Attention & Memory

Like age-related changes in brain structure and function, age-related changes in cognition are not uniform across all cognitive domains or across all older individuals. The basic cognitive functions most affected by age are attention and memory. Older adults show significant impairments on attentional tasks, particularly at multitasking. General knowledge, vocabulary, and verbal ability are not significantly declined throughout the life cycle (from early to late adulthood). But times tasks, speed of information processing, recognition memory, episodic memory, spatial abilities, and working memory decline drastically with age.

Working & Long-Term Memory

Working memory is a multidimensional cognitive platform that is considered the fundamental source of age-related deficits in a variety of cognitive tasks, including long-term memory, language, problem solving, and decision making. Work juggling, reorganization, or integration of the contents of working memory are the areas where older adults exhibit significant deficits. Differential activation of the brain in young and old adults, particularly within the prefrontal cortex, suggests people perform these tasks differently based on age.

Aging principally affects episodic memory, namely memory for specific events or experiences that occurred in the past. However, semantic memory is largely preserved in old age (which is mostly general knowledge), without specific detail, contributing to the absence of age differences.

Higher Level Cognitive Functions

Speech and language processing are largely intact in older adults under normal conditions, although processing time may be somewhat slower than in young adults. Decision-making with age is still under scientific exploration. The older generation tends to rely more on prior knowledge/experience about the problem domain and less on new information, whereas young people, who likely have less knowledge about these issues, tend to sample and evaluate more current information and consider more alternatives before making their decisions. Executive control is a multi-component construct that consists of a range of different processes that are involved in the planning, organization, coordination, implementation, and evaluation of many non-routine activities. Both structural and functional neuroimaging studies have revealed a decline in older adults in volume and function of prefrontal brain regions, supporting the decline of executive control.

Conclusion

Age-related changes in cognitive function vary considerably across individuals and across life cycle stages, with some cognitive functions appearing more susceptible than others to the effects of aging. Cognitive decline is not inevitable, and it is not uniform across domains.

For example, some older adults have excellent episodic memory function but impaired executive function, and vice versa. Some older adults retain excellent cognitive function well into their 70s and 80s and perform as well or better than younger adults.

This inter-individual variability is likely attributable to a range of factors and mechanisms—biological, psychological, health-related, environmental, and lifestyle.

Dilip Ghosh, PhD, FACN

nutriConnect

Dilip Ghosh, PhD, FACN, is director of nutriConnect, based in Sydney, Australia. He is also professionally involved with Soho Flordis International, the University of Western Sydney, Australia, and is an Honorary Ambassador with the Global Harmonization Initiative (GHI). Dr. Ghosh received his PhD in biomedical science from University of Calcutta, India. He has been involved in drug-development (both synthetic and natural) and functional food research and development both in academic and industry domains. Dr. Ghosh has published more than 70 papers in peer-reviewed journals, and he has authored three recent books: “Biotechnology in Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals,” “Innovation in Healthy and Functional Foods,” and “Clinical Perspective of Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals” under CRC Press. His next book, “Pharmaceuticals to Nutraceuticals: A Shift in Disease Prevention,” is in press. He can be reached at dilipghosh@nutriconnect.com.au; www.nutriconnect.com.au.

Brain in Old Age

The brain undergoes tremendous age-associated structural and functional changes with age. Figure 1 describes the transition of cognitive decline from normal aging to Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s disease.

A range of cognitive decline in normal aging starts in the 20s; these declines are stable at the age of 75. The most obvious is a steady decrease in brain size, an increase in ventricular spaces, and cerebrospinal fluid. The most severe effects occur in prefrontal regions, but general brain atrophy accelerates in old age via anterior-posterior gradient. Brain white matter volume is not affected that much until about age 70. Also, cerebral dopamine receptor density depletes with age, which plays a central role in regulating attention and in modulating response to contextual stimuli.

Attention & Memory

Like age-related changes in brain structure and function, age-related changes in cognition are not uniform across all cognitive domains or across all older individuals. The basic cognitive functions most affected by age are attention and memory. Older adults show significant impairments on attentional tasks, particularly at multitasking. General knowledge, vocabulary, and verbal ability are not significantly declined throughout the life cycle (from early to late adulthood). But times tasks, speed of information processing, recognition memory, episodic memory, spatial abilities, and working memory decline drastically with age.

Working & Long-Term Memory

Working memory is a multidimensional cognitive platform that is considered the fundamental source of age-related deficits in a variety of cognitive tasks, including long-term memory, language, problem solving, and decision making. Work juggling, reorganization, or integration of the contents of working memory are the areas where older adults exhibit significant deficits. Differential activation of the brain in young and old adults, particularly within the prefrontal cortex, suggests people perform these tasks differently based on age.

Aging principally affects episodic memory, namely memory for specific events or experiences that occurred in the past. However, semantic memory is largely preserved in old age (which is mostly general knowledge), without specific detail, contributing to the absence of age differences.

Higher Level Cognitive Functions

Speech and language processing are largely intact in older adults under normal conditions, although processing time may be somewhat slower than in young adults. Decision-making with age is still under scientific exploration. The older generation tends to rely more on prior knowledge/experience about the problem domain and less on new information, whereas young people, who likely have less knowledge about these issues, tend to sample and evaluate more current information and consider more alternatives before making their decisions. Executive control is a multi-component construct that consists of a range of different processes that are involved in the planning, organization, coordination, implementation, and evaluation of many non-routine activities. Both structural and functional neuroimaging studies have revealed a decline in older adults in volume and function of prefrontal brain regions, supporting the decline of executive control.

Conclusion

Age-related changes in cognitive function vary considerably across individuals and across life cycle stages, with some cognitive functions appearing more susceptible than others to the effects of aging. Cognitive decline is not inevitable, and it is not uniform across domains.

For example, some older adults have excellent episodic memory function but impaired executive function, and vice versa. Some older adults retain excellent cognitive function well into their 70s and 80s and perform as well or better than younger adults.

This inter-individual variability is likely attributable to a range of factors and mechanisms—biological, psychological, health-related, environmental, and lifestyle.

Dilip Ghosh, PhD, FACN

nutriConnect

Dilip Ghosh, PhD, FACN, is director of nutriConnect, based in Sydney, Australia. He is also professionally involved with Soho Flordis International, the University of Western Sydney, Australia, and is an Honorary Ambassador with the Global Harmonization Initiative (GHI). Dr. Ghosh received his PhD in biomedical science from University of Calcutta, India. He has been involved in drug-development (both synthetic and natural) and functional food research and development both in academic and industry domains. Dr. Ghosh has published more than 70 papers in peer-reviewed journals, and he has authored three recent books: “Biotechnology in Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals,” “Innovation in Healthy and Functional Foods,” and “Clinical Perspective of Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals” under CRC Press. His next book, “Pharmaceuticals to Nutraceuticals: A Shift in Disease Prevention,” is in press. He can be reached at dilipghosh@nutriconnect.com.au; www.nutriconnect.com.au.