11.10.20

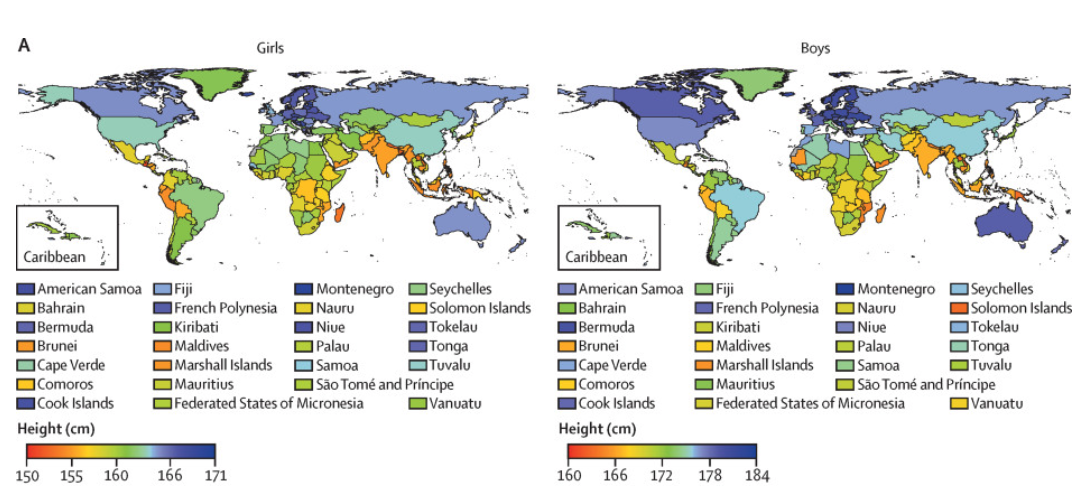

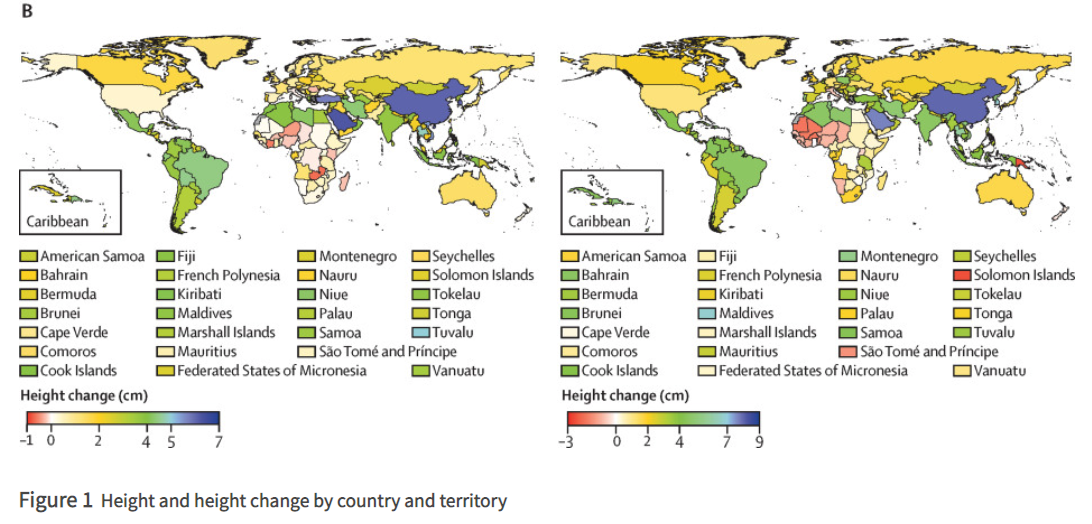

According to a new global analysis, which sourced data from 65 million children between the ages of 5 and 19 years old spread across 193 countries, there is a 20 cm (7.8 inch) height gap between the tallest and shortest 19-year-olds on average; these differences in height and BMI are indicators of disparity in the health and quality of adolescents’ diets, which vary enormously around the world. Childhood nutrition is the leading determinant of height and BMI when entering adulthood, the researchers said.

This represents an eight-year growth gap for girls – the average 19-year-old in Guatemala or Bangladesh, the two shortest countries, was the same height as the average 11-year-old girl in the Netherlands, the tallest country which has remained in this position of advantage well before the late 20th century. For boys, there was a six-year height gap.

The international team of researchers said that poor nutrition goes beyond the observed stunted growth, but that it may also lead to childhood obesity, affecting a child’s health and wellbeing for their entire life. The research, which included data compiled from populations between 1985 to 2019, found that the tallest countries were in northwest and central Europe, which included the Netherlands, Montenegro, Denmark, and Iceland. The nations with the shortest 19-year-olds were mostly in south and southeast Asia, Latin America, and East Africa, including Timor-Leste, Papua New Guinea, Guatemala, and Bangladesh.

China, South Korea, and parts of southeast Asia saw the greatest increases in height from 1985 to 2019. The average 19-year-old boy in China is now 8 cm taller than in 1985, and the nation went from being the 150thtallest to the 65thtallest in the same time span, for example. Many sub-Saharan African nations, on the other hand, either stagnated or reduced in height during the same time period.

Global height ranking in the U.K. has worsened over the past 35 years, the researchers found, with 19-year-old boys falling from 28th tallest in 1985 to 39th tallest in 2019, and 19-year-old girls falling from 42nd to 49th tallest.

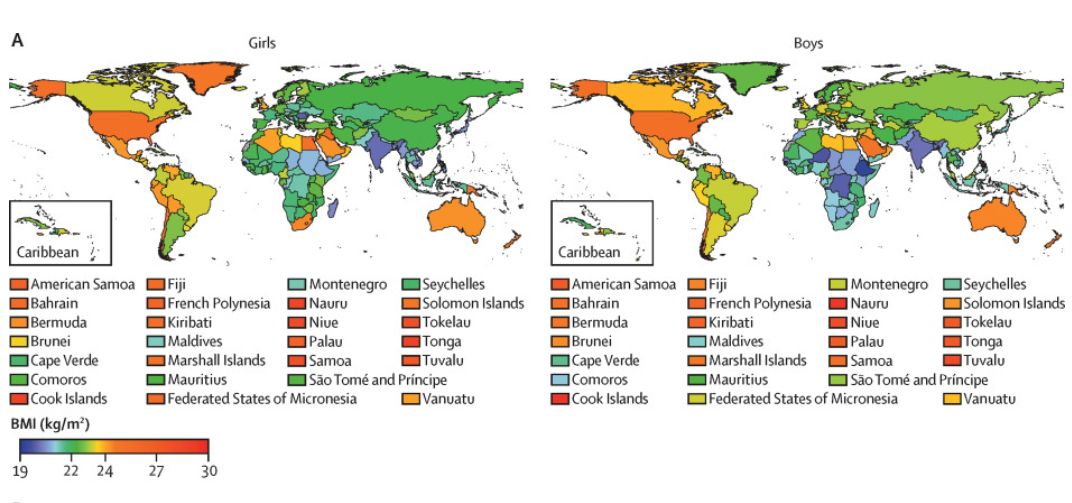

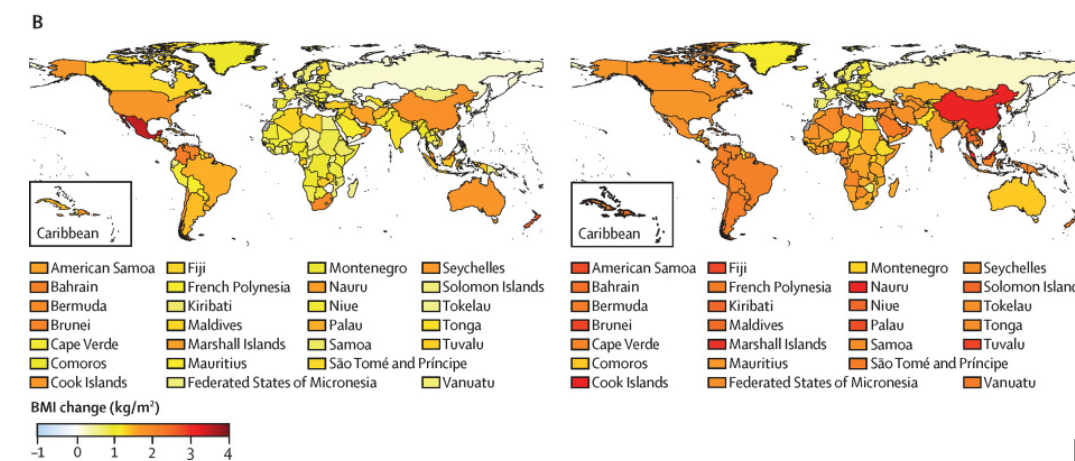

The study also analyzed BMI, a measure of height to weight ratio, and is a standard measure of whether a person is at an appropriate weight for their height. 19-year-olds with the largest BMI were found in the Pacific Islands, the U.S., the Middle East, and New Zealand, while lowest BMIs on average were found in south Asian countries such as India and Bangladesh. The gap in average BMIs between the lowest and highest was about 9 BMI units, translated to 55 pounds.

In countries which had unhealthy BMIs, either too high or low, children tended to have healthy BMIs until the age of five, when children began to experience too small an increase in height or too much of a weight gain compared to a potential for healthy growth.

“Children in some countries grow healthily to five years, but fall behind in school years,” Majid Ezzati, senior author of the study, said. “Children in some countries grow healthily to five years, but fall behind in school years. This shows that there is an imbalance between investment in improving nutrition in preschoolers, and in school-aged children and adolescents. The issue is especially important during the COVID-19 pandemic when schools are closed throughout the world, and many poor families are unable to provide adequate nutrition for their children.”

“Our findings should motivate policies that increase the availability and reduce the cost of nutritious foods, as this will help children grow taller without gaining excessive weight for their height,” Dr. Andrea Rodriguez Martinez, lead author of the study, said. “These initiatives include food vouchers toward nutritious foods for low income families, and free healthy school meal programs which are particularly under threat during the pandemic.”

This represents an eight-year growth gap for girls – the average 19-year-old in Guatemala or Bangladesh, the two shortest countries, was the same height as the average 11-year-old girl in the Netherlands, the tallest country which has remained in this position of advantage well before the late 20th century. For boys, there was a six-year height gap.

The international team of researchers said that poor nutrition goes beyond the observed stunted growth, but that it may also lead to childhood obesity, affecting a child’s health and wellbeing for their entire life. The research, which included data compiled from populations between 1985 to 2019, found that the tallest countries were in northwest and central Europe, which included the Netherlands, Montenegro, Denmark, and Iceland. The nations with the shortest 19-year-olds were mostly in south and southeast Asia, Latin America, and East Africa, including Timor-Leste, Papua New Guinea, Guatemala, and Bangladesh.

China, South Korea, and parts of southeast Asia saw the greatest increases in height from 1985 to 2019. The average 19-year-old boy in China is now 8 cm taller than in 1985, and the nation went from being the 150thtallest to the 65thtallest in the same time span, for example. Many sub-Saharan African nations, on the other hand, either stagnated or reduced in height during the same time period.

Global height ranking in the U.K. has worsened over the past 35 years, the researchers found, with 19-year-old boys falling from 28th tallest in 1985 to 39th tallest in 2019, and 19-year-old girls falling from 42nd to 49th tallest.

The study also analyzed BMI, a measure of height to weight ratio, and is a standard measure of whether a person is at an appropriate weight for their height. 19-year-olds with the largest BMI were found in the Pacific Islands, the U.S., the Middle East, and New Zealand, while lowest BMIs on average were found in south Asian countries such as India and Bangladesh. The gap in average BMIs between the lowest and highest was about 9 BMI units, translated to 55 pounds.

In countries which had unhealthy BMIs, either too high or low, children tended to have healthy BMIs until the age of five, when children began to experience too small an increase in height or too much of a weight gain compared to a potential for healthy growth.

“Children in some countries grow healthily to five years, but fall behind in school years,” Majid Ezzati, senior author of the study, said. “Children in some countries grow healthily to five years, but fall behind in school years. This shows that there is an imbalance between investment in improving nutrition in preschoolers, and in school-aged children and adolescents. The issue is especially important during the COVID-19 pandemic when schools are closed throughout the world, and many poor families are unable to provide adequate nutrition for their children.”

“Our findings should motivate policies that increase the availability and reduce the cost of nutritious foods, as this will help children grow taller without gaining excessive weight for their height,” Dr. Andrea Rodriguez Martinez, lead author of the study, said. “These initiatives include food vouchers toward nutritious foods for low income families, and free healthy school meal programs which are particularly under threat during the pandemic.”