By Gregory Stephens, RD, Trish Cadwallader & Sheila Campbell, PhD, RD01.03.19

I started my career in the nutrition industry as a hospital dietitian and administrator. For the most part, the dietary supplement industry of the 1970s was very different than today. For many companies, the level of clinical substantiation, product consistency, and quality standards was not even close to what it is now. This was a striking contrast to the hospital clinical nutrition industry, which operated closer to pharmaceutical standards. Due to a variety of market dynamics, these two industries have come closer together, making it increasingly difficult to draw a line between dietary supplements and institutional clinical nutrition products today.

The key changing dynamics include FDA intervention in supplement marketing, a more knowledgeable and savvy consumer, brands building stronger and positive awareness through well designed clinical trials, and enhanced quality standards. Accentuating this observation, I recently participated in a SupplySide West panel presentation titled “The Convergence of Food and Pharma.”

There are more medical foods and other traditional clinical nutrition products marketed by dietary supplement companies today. However, supplement companies are just beginning to market these products to healthcare institutions, hospitals, subacute care rehabilitation centers, skilled nursing facilities, and the medical home care setting.

When considering distribution channels in the nutraceutical industry, people often think of the natural foods channel, food/drug/mass/club stores, multi-level marketing (MLM), e-commerce, and the heath practitioner channel. The healthcare institutional channel has been largely untapped by supplement companies.

The use of dietary supplements in healthcare facilities is not new; however, the products administered have typically been multivitamin/mineral supplements. The broader institutional clinical nutrition market, including medical foods, is not a small, niche market, as product sales in the U.S. easily exceed $2 billion annually. The goal of this column is to provide insights into the nuances of the healthcare institutional market.

Acquisition of Clinical Nutrition Products

Securing the stocking and usage of clinical nutrition products in the U.S. healthcare system can vary by market segments: acute care, long-term care, and home healthcare. Obtaining distribution of nutritional products through a drug wholesaler such as Cardinal, McKesson, or Amerisource is not necessarily the hard part of the equation. In other words, distributors may be willing to take on a new clinical nutrition product, but then what?

Acute Care. Individual hospitals are typically a part of a collection of hospitals or healthcare systems. These systems join group purchasing organizations (GPOs) to help contain costs by obtaining competitive pricing on an array of products used in hospitals. Large manufacturers such as Abbott Nutrition and Nestlé negotiate contract pricing for their products directly with the GPOs. Based on sales generated from member hospitals, these manufacturers pay the GPOs. Key GPOs include Premier, Vizient (VHA, UHC, Novation), and Amerinet.

Once a new product is on a GPO contract, the manufacturer’s sales force often works with the hospital systems to add the new product to the formulary. If the new product can demonstrate improved patient outcomes and/or a significant cost savings to the institution, then it’s more likely the new product will be adopted. Typically, these newer entries will replace an established product on a formulary. To contain costs, hospitals keep tight controls on formularies. Once a product is added to a formulary, it is the responsibility of the manufacturer’s sales force to create awareness of and demand for the new product among the hospital physicians and clinical dietitians. Nutritional products are shipped to hospitals directly from the manufacturer or through

drug wholesalers.

Long-Term Care/Rehabilitation. In recent years, there has been a shift in the clinical nutrition product acquisition process in long-term care. Once the domain of long-term care chains contracting directly with manufacturers and serviced by durable medical equipment suppliers (DMEs), more GPOs are using and mirroring the acute care model. “Spending and participation is on the rise as the long-term care industry seeks help in controlling costs,” said Russ Ede, vice president of non-acute care, Amerinet (Journal of Healthcare Contracting, March 2018). In 2004, the St. Louis, MO-based GPO served 1,799 long-term-care members, he noted. Today, this number has grown to 3,280. “In the past, we focused more on the acute care and ambulatory/surgery center markets. Now we are focused on the long-term care market as well.”

Home Healthcare. The younger but undoubtedly fastest-growing home healthcare segment is the least consolidated of the three segments. In home healthcare, clinical nutrition products are predominately sole source or supplemental complete nutrition administered through tube feedings. These products find their way to a patient’s home through the home medical equipment supplier (HME). If the HME is associated with a hospital system, the hospital formulary will likely carry over to a patient’s home care. Independent HMEs order products directly from a nutrition manufacturer or through a drug wholesale distributor. Their choice of brand is frequently based on competitive pricing. Clinical nutrition that is not being administered through a tube feeding is typically purchased at retail by a family member.

Clinical Substantiation in Healthcare Institutions

Warren Buffet has said, “It takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it.” The quality and safety of dietary supplements have always been an issue in healthcare institutions. Within the past few years, the FDA has issued numerous warning letters to dietary supplement companies launching new medical foods. These get noticed by decision makers assessing nutritional products for inclusion on hospital and long-term care formularies.

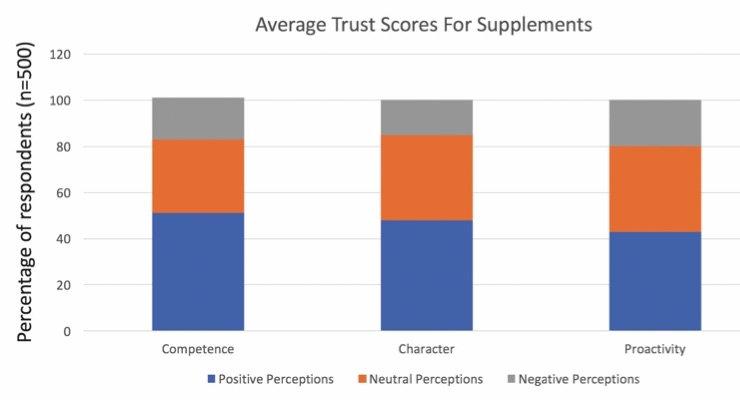

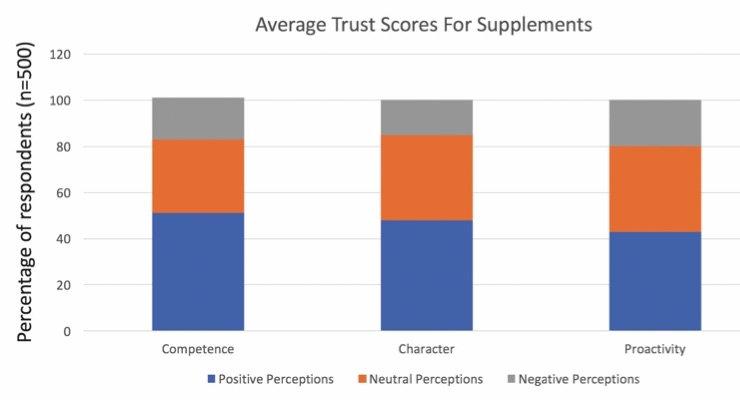

Though the quality of nutritional products in the dietary supplement industry is improving significantly, many consumers still exhibit a certain level of skepticism in their perceptions of supplement industry. A poll by NEXT and Nutrition Business Journal (NBJ) showed that many survey respondents still have relatively poor perceptions of the competence, character, and proactivity of the supplements industry (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Data points are: Competence, negative = 18%, neutral = 32%, positive = 51% Character, 15%, 37%, 48%; Proactivity, 20%, 17% 43%

Source: Nutrition Business Journal, 2016

Not surprising, skepticism is even more apparent among the majority of healthcare professionals. A social media post by a dietitian manager of Eat Well, Be Well is one example:

“If your dietary supplement [promotion] says this: ‘Green coffee beans have proven clinical studies with amazing effects on hypertension, cholesterol and weight loss!’ There is a hyperlink to ONE study, done in mice. And those ‘amazing’ effects? Seriously, I cannot find them. Note: it says ‘amazing effects’ but NOT what those effects are. The study did not look at blood pressure (maybe because they haven’t made a mouse blood pressure cuff yet?). The study looked at triglycerides, but not other markers in the lipid panel. (No significant difference between the groups.) And it did not find any significant change in weight between the groups. So, before you click to buy ... click on the research cited. It may not be saying what they imply in their marketing.”

Healthcare professionals, especially physicians, engage in evidence-based practice. Evidence-based practice uses data from well-designed research studies to guide delivery of healthcare. Evidence-based information ranges from Level A (the strongest) to Level C (the weakest).

Level A evidence comes from:

Level B evidence comes from:

Level C evidence comes from:

Healthcare professionals are accustomed to, and product claims are supported by, results from sound research studies. This does not mean that original research on a specific product is always required. It is possible to extract credible information from studies published in the medical and scientific literature on ingredients or formulations. The public may ask for proof of product efficacy. Decision makers in healthcare institutions, including physicians, will demand it.

The opportunity for distribution of nutritional products in healthcare institutions is growing dramatically. As clinical efficacy and quality improve, more dietary supplements are finding their way onto formularies. Marketers need to understand the process and expectations of decision makers in healthcare institutions as market evolution accelerates. Companies interested in assessing opportunities of institutional distribution are advised to seek counseling from a qualified consultant or other persons who have successfully launched such products. In addition to the financial benefits, providing nutritional support for the management of a range of serious health conditions is something patients and healthcare professionals value.

Gregory Stephens

Windrose Partners

Greg Stephens, RD, is president of Windrose Partners, a company serving clients in the the dietary supplement, functional food and natural product industries. Formerly vice president of strategic consulting with The Natural Marketing Institute (NMI) and Vice President of Sales and Marketing for Nurture, Inc (OatVantage), he has 25 years of specialized expertise in the nutritional and pharmaceutical industries. His prior experience includes a progressive series of senior management positions with Abbott Nutrition (Ross Products Division of Abbott Laboratories), including development of global nutrition strategies for disease-specific growth platforms and business development for Abbott’s medical foods portfolio. He can be reached at 267-432-2696; E-mail: gregstephens@windrosepartners.com.

Trish Cadwallader

Trish Cadwallader has over 30 years of medical food, consumer and international marketing and sales experience. She held a wide range of leadership positions in brand marketing, business development, marketing research and sales with Abbott Nutrition. She successfully launched several breakthrough nutritional brands and was responsible for transitioning Ensure from a hospital-based product to a mainstream consumer brand.

Sheila Campbell

Sheila Campbell, PhD, RD, has practiced in the field of clinical nutrition for more than 30 years, including 17 years with Ross Products Division of Abbott Laboratories. She has authored more than 70 publications on scientific, clinical and medical topics and has presented 60 domestic and international lectures on health-related topics. She can be reached at smcampbellphdrd@gmail.com.

The key changing dynamics include FDA intervention in supplement marketing, a more knowledgeable and savvy consumer, brands building stronger and positive awareness through well designed clinical trials, and enhanced quality standards. Accentuating this observation, I recently participated in a SupplySide West panel presentation titled “The Convergence of Food and Pharma.”

There are more medical foods and other traditional clinical nutrition products marketed by dietary supplement companies today. However, supplement companies are just beginning to market these products to healthcare institutions, hospitals, subacute care rehabilitation centers, skilled nursing facilities, and the medical home care setting.

When considering distribution channels in the nutraceutical industry, people often think of the natural foods channel, food/drug/mass/club stores, multi-level marketing (MLM), e-commerce, and the heath practitioner channel. The healthcare institutional channel has been largely untapped by supplement companies.

The use of dietary supplements in healthcare facilities is not new; however, the products administered have typically been multivitamin/mineral supplements. The broader institutional clinical nutrition market, including medical foods, is not a small, niche market, as product sales in the U.S. easily exceed $2 billion annually. The goal of this column is to provide insights into the nuances of the healthcare institutional market.

Acquisition of Clinical Nutrition Products

Securing the stocking and usage of clinical nutrition products in the U.S. healthcare system can vary by market segments: acute care, long-term care, and home healthcare. Obtaining distribution of nutritional products through a drug wholesaler such as Cardinal, McKesson, or Amerisource is not necessarily the hard part of the equation. In other words, distributors may be willing to take on a new clinical nutrition product, but then what?

Acute Care. Individual hospitals are typically a part of a collection of hospitals or healthcare systems. These systems join group purchasing organizations (GPOs) to help contain costs by obtaining competitive pricing on an array of products used in hospitals. Large manufacturers such as Abbott Nutrition and Nestlé negotiate contract pricing for their products directly with the GPOs. Based on sales generated from member hospitals, these manufacturers pay the GPOs. Key GPOs include Premier, Vizient (VHA, UHC, Novation), and Amerinet.

Once a new product is on a GPO contract, the manufacturer’s sales force often works with the hospital systems to add the new product to the formulary. If the new product can demonstrate improved patient outcomes and/or a significant cost savings to the institution, then it’s more likely the new product will be adopted. Typically, these newer entries will replace an established product on a formulary. To contain costs, hospitals keep tight controls on formularies. Once a product is added to a formulary, it is the responsibility of the manufacturer’s sales force to create awareness of and demand for the new product among the hospital physicians and clinical dietitians. Nutritional products are shipped to hospitals directly from the manufacturer or through

drug wholesalers.

Long-Term Care/Rehabilitation. In recent years, there has been a shift in the clinical nutrition product acquisition process in long-term care. Once the domain of long-term care chains contracting directly with manufacturers and serviced by durable medical equipment suppliers (DMEs), more GPOs are using and mirroring the acute care model. “Spending and participation is on the rise as the long-term care industry seeks help in controlling costs,” said Russ Ede, vice president of non-acute care, Amerinet (Journal of Healthcare Contracting, March 2018). In 2004, the St. Louis, MO-based GPO served 1,799 long-term-care members, he noted. Today, this number has grown to 3,280. “In the past, we focused more on the acute care and ambulatory/surgery center markets. Now we are focused on the long-term care market as well.”

Home Healthcare. The younger but undoubtedly fastest-growing home healthcare segment is the least consolidated of the three segments. In home healthcare, clinical nutrition products are predominately sole source or supplemental complete nutrition administered through tube feedings. These products find their way to a patient’s home through the home medical equipment supplier (HME). If the HME is associated with a hospital system, the hospital formulary will likely carry over to a patient’s home care. Independent HMEs order products directly from a nutrition manufacturer or through a drug wholesale distributor. Their choice of brand is frequently based on competitive pricing. Clinical nutrition that is not being administered through a tube feeding is typically purchased at retail by a family member.

Clinical Substantiation in Healthcare Institutions

Warren Buffet has said, “It takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it.” The quality and safety of dietary supplements have always been an issue in healthcare institutions. Within the past few years, the FDA has issued numerous warning letters to dietary supplement companies launching new medical foods. These get noticed by decision makers assessing nutritional products for inclusion on hospital and long-term care formularies.

Though the quality of nutritional products in the dietary supplement industry is improving significantly, many consumers still exhibit a certain level of skepticism in their perceptions of supplement industry. A poll by NEXT and Nutrition Business Journal (NBJ) showed that many survey respondents still have relatively poor perceptions of the competence, character, and proactivity of the supplements industry (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Data points are: Competence, negative = 18%, neutral = 32%, positive = 51% Character, 15%, 37%, 48%; Proactivity, 20%, 17% 43%

Source: Nutrition Business Journal, 2016

Not surprising, skepticism is even more apparent among the majority of healthcare professionals. A social media post by a dietitian manager of Eat Well, Be Well is one example:

“If your dietary supplement [promotion] says this: ‘Green coffee beans have proven clinical studies with amazing effects on hypertension, cholesterol and weight loss!’ There is a hyperlink to ONE study, done in mice. And those ‘amazing’ effects? Seriously, I cannot find them. Note: it says ‘amazing effects’ but NOT what those effects are. The study did not look at blood pressure (maybe because they haven’t made a mouse blood pressure cuff yet?). The study looked at triglycerides, but not other markers in the lipid panel. (No significant difference between the groups.) And it did not find any significant change in weight between the groups. So, before you click to buy ... click on the research cited. It may not be saying what they imply in their marketing.”

Healthcare professionals, especially physicians, engage in evidence-based practice. Evidence-based practice uses data from well-designed research studies to guide delivery of healthcare. Evidence-based information ranges from Level A (the strongest) to Level C (the weakest).

Level A evidence comes from:

- Rigorously designed randomized, prospective, controlled trials (RPCTs).

- Systematic review or meta-analysis of all relevant RPCTs.

- Clinical practice guidelines based on systematic reviews of RPCTs.

Level B evidence comes from:

- Well-designed, controlled trials that are not randomized. Because subjects are not randomized to experimental and control groups, this type of research is less valid than RPCTs. Results from these studies cannot be generalized outside the group that took part in the study.

- Epidemiologic studies where groups of people with the same condition are studied over a period of time. These trials are not controlled, nor is a specific intervention studied. It is impossible to clearly define what factors caused the observed outcomes.

- Case-controlled studies completed in subjects with a disease or outcome are compared with healthy subjects.

Level C evidence comes from:

- Uncontrolled studies that do not control participant selection or interventions.

- Consensus viewpoint and expert opinion where clinical experts discuss and agree on practices. This level of evidence is used when there are no studies in the area.

Healthcare professionals are accustomed to, and product claims are supported by, results from sound research studies. This does not mean that original research on a specific product is always required. It is possible to extract credible information from studies published in the medical and scientific literature on ingredients or formulations. The public may ask for proof of product efficacy. Decision makers in healthcare institutions, including physicians, will demand it.

The opportunity for distribution of nutritional products in healthcare institutions is growing dramatically. As clinical efficacy and quality improve, more dietary supplements are finding their way onto formularies. Marketers need to understand the process and expectations of decision makers in healthcare institutions as market evolution accelerates. Companies interested in assessing opportunities of institutional distribution are advised to seek counseling from a qualified consultant or other persons who have successfully launched such products. In addition to the financial benefits, providing nutritional support for the management of a range of serious health conditions is something patients and healthcare professionals value.

Gregory Stephens

Windrose Partners

Greg Stephens, RD, is president of Windrose Partners, a company serving clients in the the dietary supplement, functional food and natural product industries. Formerly vice president of strategic consulting with The Natural Marketing Institute (NMI) and Vice President of Sales and Marketing for Nurture, Inc (OatVantage), he has 25 years of specialized expertise in the nutritional and pharmaceutical industries. His prior experience includes a progressive series of senior management positions with Abbott Nutrition (Ross Products Division of Abbott Laboratories), including development of global nutrition strategies for disease-specific growth platforms and business development for Abbott’s medical foods portfolio. He can be reached at 267-432-2696; E-mail: gregstephens@windrosepartners.com.

Trish Cadwallader

Trish Cadwallader has over 30 years of medical food, consumer and international marketing and sales experience. She held a wide range of leadership positions in brand marketing, business development, marketing research and sales with Abbott Nutrition. She successfully launched several breakthrough nutritional brands and was responsible for transitioning Ensure from a hospital-based product to a mainstream consumer brand.

Sheila Campbell

Sheila Campbell, PhD, RD, has practiced in the field of clinical nutrition for more than 30 years, including 17 years with Ross Products Division of Abbott Laboratories. She has authored more than 70 publications on scientific, clinical and medical topics and has presented 60 domestic and international lectures on health-related topics. She can be reached at smcampbellphdrd@gmail.com.