Case Adams, Contributing Writer11.01.12

There was a time when fiber was mostly about constipation. Then came findings that fiber increases glucose control and helps prevent type 2 diabetes. This was followed by research showing fiber has cardiovascular benefits, including cholesterol reduction.

Now a new reality has taken hold: Many fibers are in fact prebiotic, and therein may lie a major reason why they are so beneficial. Fiber is feed for our gut’s microorganisms.

“Prebiotic fibers are now incorporated into a wide range of food ingredients and therefore are becoming a big part of everyday diets,” said Glenn Gibson, PhD, professor of Food Microbial Sciences at the U.K.’s University of Reading.

This summer, Dr. Gibson and associates conducted a study of 55 healthy adults to determine the prebiotic role of arabinoxylan-oligosaccharide—a component of wheat bran. After three weeks of eating the bran extract in breakfast cereal, the research found arabinoxylan-oligosaccharide significantly increases bifidobacteria colonies in a dose-dependent manner1.

Dr. Gibson also led a study of 40 adults and found arabinoxylan-oligosaccharide increases lactobacilli probiotic populations2.

Dr. Gibson’s research has tested a multitude of probiotic species and their response to prebiotic fibers. “Currently, the main prebiotic targets are bifidobacteria and lactobacilli; however, more genera may be soon included, such as roseburia, eubacteria faecalibacteria,” projected Dr. Gibson.

The research has also linked prebiotic fibers to probiotic benefits. Many of these benefits are anti-inflammatory. “When the bacteria utilize the right fiber for their energy, they produce anti-inflammatory compounds called short chain fatty acids,” said Mark Cisneros, PhD, CEO of Nutrabiotix LLC.

Dr. Gibson suggests future prebiotic fibers research will study their anti-inflammatory benefits. “Health aspects of prebiotic fibers should be determined in human trials targeting major ailments suffered by consumers, such as ulcerative colitis, obesity, autism, gastroenteritis and irritable bowel syndrome.”

As we unfold the connection between fiber and our digestive bacteria, these dots are becoming connected by consumers and manufacturers alike.

According to data from SPINS, Schaumburg, IL, combined U.S. sales of prebiotics and probiotics (excluding Whole Foods) are up 17% over last year.

The prebiotic revolution has fueled continued growth in the dietary fiber market. According to Nutrition Business Journal(Boulder, CO) estimates, U.S. consumer sales of psyllium supplements alone reached $120 million in 2011 on 6% growth.

SPINS data shows psyllium sales are growing faster in 2012, with 9% growth over 2011. Flaxseed sales have grown at an even higher (23%) rate to nearly $13 million. This growth level is mirrored by chia seed, with 25% growth to nearly $300,000, fructooligosaccharides (FOS) up 21% to $6.8 million and triphala at 19% growth to $171,679, according to SPINS data (all excluding Whole Foods).

Worldwide fiber sales are also expanding rapidly. A 2012 study from Global Industry Analysts, San Jose, CA, determined that the global market for high fiber and whole grain foods will exceed $27 billion a year by 2017.

Most experts feel there is still plenty of room for future growth. “The Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 advise that adults consume between 25–30 grams of fiber a day, yet the average American consumes only 14 to 15 grams of dietary fiber on a daily basis,” noted Harold Nicoll, APR of TIC Gums, Inc., White Marsh, MD.

The Rise of the Fermentable Fibers

The World Health Organization’s Food and Agriculture Organization defines dietary fiber as polysaccharides with 10 or more monomeric units not hydrolyzed by endogenous hormones in the small intestine. And the American Association of Cereal Chemists considers fiber neither digested nor absorbed in the small intestine.

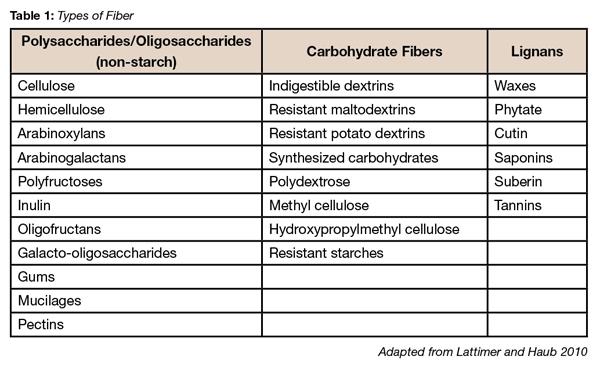

Fiber has typically been divided into two general forms: soluble and insoluble. These now include oligosaccharides, inulins, pectins, beta-glucans, lignans, resistant starches and many others (see Table 1).

The mounting distinction among these non-digestible polysaccharides is their fermentability. Because fermentation takes place when bacteria feed, a fermentable fiber is essentially food for intestinal probiotics.

The notion of fermentable fibers overshadows the soluble versus insoluble distinction, because both insoluble and soluble fibers can be fermentable—though soluble is more easily fermented. For example, insoluble resistant starch is fermentable, as is soluble inulin. And most whole plant fibers contain both soluble and insoluble fiber.

This distinction is proving critical to the health benefits derived from fiber. “Beneficial bacteria living in the human intestine are a key element of a healthy digestive system and overall health and wellness,” said Mr. Nicoll.

Beyond these terms is the USDA’s definition of functional fiber: an isolated form of fiber that can be supplemented into the diet3. Within this definition we find numerous innovations among suppliers to deliver what we can now coin functional fermentable fibers for use as healthy food additives or supplements.

One of the reasons probiotics prefer certain fermentables relates to their polysaccharide size and enzymes. “Fructooligosaccharides and galactooligosaccharides have different structures but are favorable toward enzymes harbored by bifidobacteria—the usual current targets for prebiotics. The same bacteria seem to prefer the kind of size of oligosaccharides,” explained Dr. Gibson.

Expanded Benefits

Confirmed clinical benefits of dietary fiber include lowered risks of heart disease, diabetes, obesity, stroke, ulcer, acid reflux, diverticulitis, hemorrhoids and others. While a balance of insoluble and soluble fibers appears to be necessary for some of these effects, fermentable soluble fibers specifically lower blood pressure, reduce glycemic and insulin response, lower colon cancer risk and lower LDL cholesterol4.

So far, four types of fiber have shown cholesterol reduction: psyllium fiber (Plantago ovata/Plantago psyllium); pectin from citrus and other fruits; galactomannan or guar gum from the Cyamopsis tetragonolobus tree; and (1,3)(1,4)-beta-D-glucans from cereal grain cell walls. Researchers from The Netherlands’ Maastricht University calculated from multiple studies that serum total cholesterol was reduced by an average of .028 mmo/L and LDL cholesterol reduced an average of .029 mmo/L for every gram of additional soluble fiber added to the diet5.

These same effects have also been seen among probiotic research, pointing to the fermentability of fiber. As research increasingly connects prebiotic fiber to probiotic colonization, many other probiotic benefits will apply to fermentable fibers. Dr. Gibson sees this research on the horizon. “The use of carefully planned human intervention studies and a growing range of prebiotic substrates can help this area expand.”

Leading prebiotic manufacturers have helped further this inquiry. Neelesh Varde, Roquette America, Inc., Geneva, IL, explained the company’s research. “We’ve been studying the effect of Nutriose on gut microflora for several years. The scientific community suggests a good prebiotic should increase the concentration of good bacteria, decrease the concentration of bad bacteria and have some sort of other physiological benefit. Our studies show examples of all three points.”

More than 200 studies now support the role of short chain fatty acids produced by fermentable fiber. “The production of short chain fatty acids in the gastrointestinal tract helps nourish the gut tissues through which minerals are absorbed, and at the same time lowers pH to an optimal level for ionizing and solubilizing minerals, thereby enhancing their absorption,” said Patrick Luchsinger of Ingredion Incorporated, Westchester, IL, producer of a short-chain FOS fermentable called Nutraflora.

Fermentable Satiety

Curbing appetite by increasing satiety is one of the most studied effects of fiber, with multiple studies illustrating an ability of different fibers to curb appetite.

“Satiating foods can reduce the urge to snack or eat between meals and lead to long-term weight management,” suggested Roquette’s Mr. Varde. “Fibers have long been thought to aid in satiety, but with the obesity problem rapidly becoming an epidemic, clinical studies are evaluating fiber as a tool to aid in satiety and weight management.”

Pam Stauffer, with Cargill, Minneapolis, MN, agreed, offering that the research shows “diets rich in fiber, such as inulin, may help maintain a feeling of fullness, or satiety, longer after eating.”

But controversy has arisen from three studies, including one published in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics this summer6. In this study, 22 adult women were given one of four different functional fiber ingredients added to chocolate bars. None of the doses—10 grams of oligofructose, inulin, soluble corn fiber or resistant wheat starch—produced a subjective increase in satiety the next morning after the dose. This finding confirmed another study published a year earlier using 5 or 8 grams of scFOS fiber given in a chocolate chew to 20 healthy human subjects7.

Another study from The Netherlands involving 21 healthy human subjects had the same results in 2009, testing barley beta-glucan and FOS8.

These studies raise an important question: Is one day of prebiotic feeding enough to provoke a meaningful change in the gut’s microorganism populations to produce an increase in satiety hormones?

The answer may come from numerous longer studies showing fermentable fibers increasing satiety. For example, a study from the Catholic University of Louvain, France, included 10 healthy adults who were given 16 grams of prebiotic per day or a placebo for two weeks. The subjects were tested for hydrogen excretion through the breath as well as plasma glucagon-like peptides. These measurements confirmed the subjects’ feelings of satiety after meals9.

An extensive review of multiple studies from the University of Calgary found that fermentable prebiotic fibers promote the gut’s probiotics, and this correlated with increases in satiety hormones10. Another review involving the University of Reading’s Dr. Gibson had similar findings11.

Mr. Varde offered results from Roquette’s research. “We’ve conducted a few studies on satiety and weight management. What we’ve found is that 8 grams per day of Nutriose imparts a feeling of satiety in adults.” These results have also been dose-dependent. “With increasing Nutriose consumption, the subjects take in fewer calories. At a level of 14 grams a day, the satiety is enough to have a statistically significant effect on weight management.”

Tom Jorgens, president of Crookston, MN-based PolyCell Technologies, clarified the satiety mechanisms of beta-D-glucans fiber. “Research from the Imperial College in London and University of Naples has found that short chain fatty acids created by fermentation activate endothelial cells in the colon to release satiety hormones such as PYY, GLP-1, GIP. These travel to the brain’s satiety centers and dampen further eating. They also decrease hunger hormones such as ghrelin.”

Research using PolyCell’s barley extract has been consistent with this mechanism. “Subjects consuming beta-glucan soluble fiber from barley in muffins lost an average of two pounds a month, while the control group consuming wheat bran muffins gained an average of two pounds per month in a University of Minnesota clinical trial with 60 subjects,” Mr. Jorgens explained.

Glycemic effects appear to be involved as well. “Overweight adult women showed a significant reduction in peak blood-sugar levels when consuming two grams of barley beta-glucan in a USDA trial. Weight loss and satiety were closely associated with longer glycemic cycles,” Mr. Jorgens added.

Gum Fibers & Dysphagia

Millions of Americans suffer difficulty swallowing both liquids and solids. For these, the importance of functional, fermentable fiber is critical.

TIC Gums’ Mr. Nicolls said that choking can occur from swallowing the thinnest of liquids, like water. Of those, more have trouble swallowing liquids than solids. “Until the middle of the last decade, the most common approach to thicken liquids and pureed foods was to provide agglomerated starch in packets or spoonable containers. However, those same powders may contribute to trouble swallowing.”

TIC Gums supplies an array of conventional and organic gum fibers, such as guar, carrageenan, pectin, locust bean gum, tara gum, acacia and agar using a multitude of different gum systems.

“One common approach to aiding consumption of beverages and foods is thickening them with starch and/or gums. Starch, gums and gums systems, known as hydrocolloids, can add viscosity to liquids and foods, stimulating saliva production and enabling better swallowing,” Mr. Nicolls added.

Inulin: Functional Fermentable

Inulin is a functional fermentable fiber and the subject of significant research. “Inulin helps promote digestive health by stimulating the normal, beneficial bacteria in the digestive tract. Studies have shown that 5 grams of inulin per day help to maintain a healthy digestive tract due to its prebiotic properties,” said Cargill’s Ms. Stauffer.

Cargill’s inulin ingredient, Oliggo-Fiber, is produced from chicory root, one of the best natural sources of inulin. “Chicory fiber promotes the growth of beneficial microflora in the digestive system helping to maintain natural balance,” explained Ms. Stauffer.

This fermentable also has glycemic benefits. “Inulin does not significantly impact blood-sugar levels and is suitable for use in a low glycemic diet,” Ms. Stauffer added.

Fermented Flax

Flaxseed is a quintessential fiber, and its success is related to its fermentability and excellent phytonutrient content. “It’s an important emerging food ingredient due to its rich content of omega 3 alpha linolenic fatty acids (ALA), lignans and fiber,” said Marilyn Stieve of leading flax fiber supplier Glanbia Nutritionals, Fitchburg, WI. “The EFAs (essential fatty acids) contribute to cardiovascular health.”

Glanbia Nutritionals has partnered with The Flax Council of Canada to provide an extensive, updated Flax Research Database for Human Health and Nutrition.

“A unique property of flaxseed is that it contains a gum matrix, known as gum mucilage,” said Ms. Stieve. “Using specially developed processing systems, functional flaxseed products have now been developed that exploit this inherent property.” Glanbia’s flaxseed-based fiber can serve as a functional guar gum replacer.

Rice Hulls: Waste Stream to Prebiotic

Ontario, Canada-based SunOpta Ingredients recently launched a gluten-free fermentable fiber made from rice hulls—normally considered a waste product.

“Being able to use plant material that would normally become part of a waste stream is a sustainable practice,” said Laura Cooper of the SunOpta Ingredients Group. “Rice hulls are very high in silica so SunOpta developed a proprietary hydrothermal process to reduce the silica and produce a soft, flexible fiber. Rice fiber is gluten-free, greater than 90% fiber and is consumer friendly in an ingredient statement. This product is self-affirmed GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe).”

Beta-Glucans

The polysaccharide (1,3)(1,4)-beta-D-glucans molecule resides in cell walls throughout the bran and endosperm of barley, oats, and to a lesser degree, some wheats. In 2002, FDA announced that beta-D-glucans soluble fiber provides cardiovascular benefits12. One of the key mechanisms cited was beta-D-glucans’ ability to inhibit bile acid absorption.

Raw oats and barley range 3-7% beta-D-glucans content, and some barley varieties can be as high as 12%. PolyCell Technologies has developed a barley-based concentrate of beta-D-glucans—marketed by partner SunOpta—averaging 28% beta-D-glucans.

“Our product is known for heart healthy cholesterol reduction, and has a very low Glycemic Index that decreases blood sugar peaks and extends glycemic cycles,” said PolyCell’s Mr. Jorgens.

“The research shows barley beta-glucan forms a viscous matrix that traps some of the cholesterol, bile acids, fats and excess sugars found in the small intestine. As the beta-glucans are fermented in the colon, most of the entrapped materials are on path to exit the body,” he explained.

Fermentable Ayurveda

The ancient science of Ayurveda has utilized fermentables for many centuries through famous digestive formulations such as triphala and chyawanprash.

Amla is common to both formulations. “Amla fruits are rich in fiber content, contributing to the digestive benefits of triphala,” noted Dr. Anurag Pande, vice president of scientific affairs, Sabinsa Corporation, East Windsor, NJ. “Though amla fruit is well known for its antioxidant and other health protective benefits, our amla fiber product concentrates amla’s fiber benefits. Amla’s insoluble fibers help absorb water and create bulk, helping conditions such as constipation.”

Fenugreek seed is another traditional Ayurvedic remedy. “Fenugreek seeds are well known for their anti-diabetic benefits,” said Dr. Pande. “The fiber fraction of fenugreek seeds consists of galactomannans—made up of galactose and mannose units.” Sabinsa’s Fenufiber is an enriched fraction from fenugreek seeds.

A University of Georgia study found fenugreek seed fiber reduced bloating and other gastrointestinal disturbances13. “The results were due to fermentation by GI microflora,” explained Dr. Pande. This study also proved psyllium husk and wheat bran to be fermentables.

Innovative Fermentables

Customers are beginning to see a need for functional, fermentable fibers. “Novel prebiotic fibers are gaining popularity among consumers because there is broader understanding of how the good bacteria in our guts help to support a healthy digestive and immune system,” said Ingredion’s Mr. Luchinger.

Ingredion’s flagship fiber ingredient is Nutraflora, an scFOS, natural prebiotic fiber. “NutraFlora is derived from non-GMO beet or cane sugar using a patented process and a traditional natural fermentation method,” Mr. Luchinger noted.

Roquette also provides several functional, fermentable fibers. “Our hallmark product in the Nutriose line is made from non-GMO corn or wheat,” said the company’s Mr. Varde. “It is 85% fiber, sugar-free and invisible—having no taste or sweetness. It dissolves rapidly in water and imparts almost negligible viscosity in liquids.”

Along with other blended fibers, North Tonawanda, NY-based International Fiber Corp. (IFC) offers a blended cellulose and inner pea fiber. “This fiber blend provides a water holding capacity of three to nine times its own weight,” said IFC’s R&D project leader Fon V. Tuntivanich, PhD. “In addition to binding water through hydrogen bonding, this fiber can also bind additional amounts of water through capillary action.”

Fiber intolerance can be an issue when building fiber intake. “One of the most interesting attributes of Nutriose is its high dietary tolerance. Our clinical studies show that 45 grams/day of Nutriose can be consumed without any major side effects,” Mr. Varde noted.

Research led by Bruce Hamaker, PhD, a food science professor at Purdue University, has resulted in a new fermentable: a natural corn-derived product entrapped in alginate. Dr. Hamaker and Dr. Ali Keshavarzian from the Rush University Medical Center have determined through their research that the alginate microbeads slowly ferment as they reach the lower intestines.

The Purdue research evolved from a quest to find a more tolerable prebiotic fiber. “Intolerance to most prebiotic fiber is primarily produced from rapid fermentation. This takes place as our gut’s bacteria extract energy from the fiber. Depending upon the quantity and how quickly it ferments, practically everyone is affected by some fiber intolerance,” explained Dr. Hamaker.

Nutrabiotix’ Dr. Cisneros described the patent-pending fermentable’s intestinal efficacy. “Tolerability allows for increased dietary fiber ingestion and targeted action to the entire colon. This increases the good bacteria in the large intestine. As these bacteria use the fiber as their energy source, they produce fermentation products that decrease inflammation and provide a healthy large intestine environment.”

According to Dr. Cisneros, the new fiber ingredient affects the “far reaches of the distal colon where our diets tend to produce a region devoid of nutrients.”

Integrating Fermentables

Incorporating these effects into foods and beverages is made easier by this wave of new functional fermentables. “Consumers are expecting more healthful paybacks from the foods they already consume regularly,” noted TIC Gum’s Mr. Nicoll.

Fiber content is only one dimension of functional fibers. “Consumers are looking for benefits beyond just fiber. Inulin-based fiber is different from many traditional soluble fibers. It has unique, important health and functional benefits. Breads and other baked goods, ice cream, bars, beverages and many other product applications have been used with it,” said Cargill’s Ms. Stauffer.

IFC’s Dr. Tuntivanich sees functional, fermentable fibers as important considerations for childhood diet and obesity problems. “The U.S. national school lunch and breakfast programs have new objectives to reduce the level of saturated fat in meals in order to supply students with appropriate calorie levels. Fiber can be used to replace some meat ingredients originally contributing to saturated fat while maintaining good taste.”

The new functional fibers are versatile. “We have customers using our product in nutritional beverages—in both RTD (ready-to-drink) and dry mixes—supplement powders, weight loss powders and tablets and capsules,” said Ingredion’s Mr. Luchsinger. “Because Nutraflora remains stable in many processing conditions such as pasteurization, batch cooking, retorting, baking, extrusion, shear drying and so on, there are many different ingredient uses such as retail smoothies, gummy and confection applications, cold cereal and nutritional bar products and yogurt and dairy-based beverages.”

The newest gums also blend well with beverages. “Ticaloid products hydrate rapidly and disperse easily,” said Mr. Nicoll. “Also important is the minimal impact these gums and gum systems have on flavor.”

Flaxseed’s gums also provide functional blending capability, according to Glanbia’s Ms. Stieve. “Flax ingredient solutions with strong water-binding capabilities and gum mucilage can be used to replace gum systems in food applications such as gluten-free baked goods, where it can improve both texture and shelf life in gluten-free tortillas, sheeted doughs, batters, breadings, sweet baked goods and fresh breads. Gums or hydrocolloid systems that help manage moisture content are essential for gluten-free baked goods, since the flours that can be used tend to dry out food formulations.”

Dr. Tuntivanich noted that some fibers can be blended with dried ingredients before use. “In some special cases, fibers may need to be hydrated before use. The benefit of using IFC fibers is that fibers can absorb the aqueous phase almost instantly, therefore, reducing the overall production time. Fibers also help to retain moisture or reduce water loss from a product; thus providing a superior, less oily texture.”

Functional fiber can also help increase shelf life, he added. “These fibers bind both water and fat, therefore stabilizing the product structure and reducing water and fat loss during cooking. Special fiber blends can help to stabilize deterioration of product texture due to cryogenic damage and fluctuating temperature storage.”

“Rice fiber can be used to increase the fiber content of baked goods, snacks and nutrition bars,” added SunOpta’s Ms. Cooper.

Nutrabiotix’ new fiber product from Purdue also has numerous applications. “We’ve designed the product to be used in several different types of formulations,” explained Dr. Cisneros. “We have used encapsulated products in our clinical studies. We’ve done preliminary formulation testing in bars and in yogurts; and other formulations such as cereals, dairy products and a host of other foods and beverages are possible.”

Researchers and ingredient suppliers are now working together to utilize the science to feed our probiotics. The University of Reading’s Dr. Gibson discussed future research in this area. “Our ongoing studies will involve metabonomics, whereby biological fluids can be subject to NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance) profiling to determine all the metabolites present.”

Dr. Gibson underscored the seriousness of the prebiotic mission with respect to global health. “As gastrointestinal disorders are prevalent worldwide, prebiotics can provide an important role in the prophylactic management of various acute and chronic gut-derived conditions.”

About the author: Case Adams is a California Naturopath and holds a PhD in Natural Health Sciences. He has written 20 books on natural health, including two books on probiotics. He can be contacted at case@caseadams.com.

References

1. Maki KC, Gibson GR, Dickmann RS, Kendall CW, Oliver Chen CY, Costabile A,

Comelli EM, McKay DL, Almeida NG, Jenkins D, Zello GA, Blumberg JB. Digestive and physiologic effects of a wheat bran extract, arabino-xylan-oligosaccharide, in breakfast cereal. Nutrition. 2012 Jul 6.

2. Walton GE, Lu C, Trogh I, Arnaut F, Gibson GR. A randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled cross-over study to determine the gastrointestinal effects of consumption of arabinoxylanoligosaccharides enriched bread in healthy volunteers. Nutr J. 2012 Jun 1;11(1):36.

3. A Report of the Panel on Macronutrients, Subcommittees on Upper Reference Levels of Nutrients and Interpretation and Uses of Dietary Reference Intakes, Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes. "7 Dietary, Functional, and Total Fiber." Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2005.

4. Anderson JW, Baird P, Davis RH Jr, Ferreri S, Knudtson M, Koraym A, Waters V, Williams CL. Health benefits of dietary fiber. Nutr Rev. 2009 Apr;67(4):188-205; Lattimer JM, Haub MD. Effects of dietary fiber and its components on metabolic health. Nutrients. 2010 Dec;2(12):1266-89; Roberfroid M, Gibson GR, Hoyles L, McCartney AL, Rastall R, Rowland I, Wolvers D, Watzl B, Szajewska H, Stahl B, Guarner F, Respondek F, Whelan K, Coxam V, Davicco MJ, Léotoing L, Wittrant Y, Delzenne NM, Cani PD, Neyrinck AM, Meheust A. Prebiotic effects: metabolic and health benefits. Br J Nutr. 2010 Aug;104 Suppl 2:S1-63.

5. Theuwissen E, Mensink RP. Water-soluble dietary fibers and cardiovascular disease. Physiol Behav. 2008 May 23;94(2):285-92.

6. Karalus M, Clark M, Greaves KA, Thomas W, Vickers Z, Kuyama M, Slavin J. Fermentable fibers do not affect satiety or food intake by women who do not practice restrained eating. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 Sep;112(9):1356-62.

7. Hess JR, Birkett AM, Thomas W, Slavin JL. Effects of short-chain fructooligosaccharides on satiety responses in healthy men and women. Appetite. 2011 Feb;56(1):128-34. Epub 2010 Dec 10.

8. Peters HP, Boers HM, Haddeman E, Melnikov SM, Qvyjt F. No effect of added beta-glucan or of fructooligosaccharide on appetite or energy intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Jan;89(1):58-63.

9. Cani PD, Lecourt E, Dewulf EM, Sohet FM, Pachikian BD, Naslain D, De Backer F, Neyrinck AM, Delzenne NM. Gut microbiota fermentation of prebiotics increases satietogenic and incretin gut peptide production with consequences for appetite sensation and glucose response after a meal. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Nov;90(5):1236-43.

10. Parnell JA, Reimer RA. Prebiotic fiber modulation of the gut microbiota improves risk factors for obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Gut Microbes. 2012 Jan-Feb;3(1):29-34.

11. Brownawell AM, Caers W, Gibson GR, Kendall CW, Lewis KD, Ringel Y, Slavin JL. Prebiotics and the health benefits of fiber: current regulatory status, future research, and goals. J. Nutr. 2012 May; 142(5):962-74.

12. Food and Drug Administration, HHS. Food labeling: health claims; soluble dietary fiber from certain foods and coronary heart disease. Interim final rule. Fed Regist. 2002 Oct 2;67(191):61773-83.

13. Al-Khaldi SF, Martin SA, Prakash L. Fermentation of fenugreek fiber, psyllium husk, and wheat bran by Bacteroides ovatus V975. Curr Microbiol. 1999 Oct;39(4):231-2.

Now a new reality has taken hold: Many fibers are in fact prebiotic, and therein may lie a major reason why they are so beneficial. Fiber is feed for our gut’s microorganisms.

“Prebiotic fibers are now incorporated into a wide range of food ingredients and therefore are becoming a big part of everyday diets,” said Glenn Gibson, PhD, professor of Food Microbial Sciences at the U.K.’s University of Reading.

This summer, Dr. Gibson and associates conducted a study of 55 healthy adults to determine the prebiotic role of arabinoxylan-oligosaccharide—a component of wheat bran. After three weeks of eating the bran extract in breakfast cereal, the research found arabinoxylan-oligosaccharide significantly increases bifidobacteria colonies in a dose-dependent manner1.

Dr. Gibson also led a study of 40 adults and found arabinoxylan-oligosaccharide increases lactobacilli probiotic populations2.

Dr. Gibson’s research has tested a multitude of probiotic species and their response to prebiotic fibers. “Currently, the main prebiotic targets are bifidobacteria and lactobacilli; however, more genera may be soon included, such as roseburia, eubacteria faecalibacteria,” projected Dr. Gibson.

The research has also linked prebiotic fibers to probiotic benefits. Many of these benefits are anti-inflammatory. “When the bacteria utilize the right fiber for their energy, they produce anti-inflammatory compounds called short chain fatty acids,” said Mark Cisneros, PhD, CEO of Nutrabiotix LLC.

Dr. Gibson suggests future prebiotic fibers research will study their anti-inflammatory benefits. “Health aspects of prebiotic fibers should be determined in human trials targeting major ailments suffered by consumers, such as ulcerative colitis, obesity, autism, gastroenteritis and irritable bowel syndrome.”

As we unfold the connection between fiber and our digestive bacteria, these dots are becoming connected by consumers and manufacturers alike.

According to data from SPINS, Schaumburg, IL, combined U.S. sales of prebiotics and probiotics (excluding Whole Foods) are up 17% over last year.

The prebiotic revolution has fueled continued growth in the dietary fiber market. According to Nutrition Business Journal(Boulder, CO) estimates, U.S. consumer sales of psyllium supplements alone reached $120 million in 2011 on 6% growth.

SPINS data shows psyllium sales are growing faster in 2012, with 9% growth over 2011. Flaxseed sales have grown at an even higher (23%) rate to nearly $13 million. This growth level is mirrored by chia seed, with 25% growth to nearly $300,000, fructooligosaccharides (FOS) up 21% to $6.8 million and triphala at 19% growth to $171,679, according to SPINS data (all excluding Whole Foods).

Worldwide fiber sales are also expanding rapidly. A 2012 study from Global Industry Analysts, San Jose, CA, determined that the global market for high fiber and whole grain foods will exceed $27 billion a year by 2017.

Most experts feel there is still plenty of room for future growth. “The Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 advise that adults consume between 25–30 grams of fiber a day, yet the average American consumes only 14 to 15 grams of dietary fiber on a daily basis,” noted Harold Nicoll, APR of TIC Gums, Inc., White Marsh, MD.

The Rise of the Fermentable Fibers

The World Health Organization’s Food and Agriculture Organization defines dietary fiber as polysaccharides with 10 or more monomeric units not hydrolyzed by endogenous hormones in the small intestine. And the American Association of Cereal Chemists considers fiber neither digested nor absorbed in the small intestine.

Fiber has typically been divided into two general forms: soluble and insoluble. These now include oligosaccharides, inulins, pectins, beta-glucans, lignans, resistant starches and many others (see Table 1).

The mounting distinction among these non-digestible polysaccharides is their fermentability. Because fermentation takes place when bacteria feed, a fermentable fiber is essentially food for intestinal probiotics.

The notion of fermentable fibers overshadows the soluble versus insoluble distinction, because both insoluble and soluble fibers can be fermentable—though soluble is more easily fermented. For example, insoluble resistant starch is fermentable, as is soluble inulin. And most whole plant fibers contain both soluble and insoluble fiber.

This distinction is proving critical to the health benefits derived from fiber. “Beneficial bacteria living in the human intestine are a key element of a healthy digestive system and overall health and wellness,” said Mr. Nicoll.

Beyond these terms is the USDA’s definition of functional fiber: an isolated form of fiber that can be supplemented into the diet3. Within this definition we find numerous innovations among suppliers to deliver what we can now coin functional fermentable fibers for use as healthy food additives or supplements.

One of the reasons probiotics prefer certain fermentables relates to their polysaccharide size and enzymes. “Fructooligosaccharides and galactooligosaccharides have different structures but are favorable toward enzymes harbored by bifidobacteria—the usual current targets for prebiotics. The same bacteria seem to prefer the kind of size of oligosaccharides,” explained Dr. Gibson.

Expanded Benefits

Confirmed clinical benefits of dietary fiber include lowered risks of heart disease, diabetes, obesity, stroke, ulcer, acid reflux, diverticulitis, hemorrhoids and others. While a balance of insoluble and soluble fibers appears to be necessary for some of these effects, fermentable soluble fibers specifically lower blood pressure, reduce glycemic and insulin response, lower colon cancer risk and lower LDL cholesterol4.

So far, four types of fiber have shown cholesterol reduction: psyllium fiber (Plantago ovata/Plantago psyllium); pectin from citrus and other fruits; galactomannan or guar gum from the Cyamopsis tetragonolobus tree; and (1,3)(1,4)-beta-D-glucans from cereal grain cell walls. Researchers from The Netherlands’ Maastricht University calculated from multiple studies that serum total cholesterol was reduced by an average of .028 mmo/L and LDL cholesterol reduced an average of .029 mmo/L for every gram of additional soluble fiber added to the diet5.

These same effects have also been seen among probiotic research, pointing to the fermentability of fiber. As research increasingly connects prebiotic fiber to probiotic colonization, many other probiotic benefits will apply to fermentable fibers. Dr. Gibson sees this research on the horizon. “The use of carefully planned human intervention studies and a growing range of prebiotic substrates can help this area expand.”

Leading prebiotic manufacturers have helped further this inquiry. Neelesh Varde, Roquette America, Inc., Geneva, IL, explained the company’s research. “We’ve been studying the effect of Nutriose on gut microflora for several years. The scientific community suggests a good prebiotic should increase the concentration of good bacteria, decrease the concentration of bad bacteria and have some sort of other physiological benefit. Our studies show examples of all three points.”

More than 200 studies now support the role of short chain fatty acids produced by fermentable fiber. “The production of short chain fatty acids in the gastrointestinal tract helps nourish the gut tissues through which minerals are absorbed, and at the same time lowers pH to an optimal level for ionizing and solubilizing minerals, thereby enhancing their absorption,” said Patrick Luchsinger of Ingredion Incorporated, Westchester, IL, producer of a short-chain FOS fermentable called Nutraflora.

Fermentable Satiety

Curbing appetite by increasing satiety is one of the most studied effects of fiber, with multiple studies illustrating an ability of different fibers to curb appetite.

“Satiating foods can reduce the urge to snack or eat between meals and lead to long-term weight management,” suggested Roquette’s Mr. Varde. “Fibers have long been thought to aid in satiety, but with the obesity problem rapidly becoming an epidemic, clinical studies are evaluating fiber as a tool to aid in satiety and weight management.”

Pam Stauffer, with Cargill, Minneapolis, MN, agreed, offering that the research shows “diets rich in fiber, such as inulin, may help maintain a feeling of fullness, or satiety, longer after eating.”

But controversy has arisen from three studies, including one published in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics this summer6. In this study, 22 adult women were given one of four different functional fiber ingredients added to chocolate bars. None of the doses—10 grams of oligofructose, inulin, soluble corn fiber or resistant wheat starch—produced a subjective increase in satiety the next morning after the dose. This finding confirmed another study published a year earlier using 5 or 8 grams of scFOS fiber given in a chocolate chew to 20 healthy human subjects7.

Another study from The Netherlands involving 21 healthy human subjects had the same results in 2009, testing barley beta-glucan and FOS8.

These studies raise an important question: Is one day of prebiotic feeding enough to provoke a meaningful change in the gut’s microorganism populations to produce an increase in satiety hormones?

The answer may come from numerous longer studies showing fermentable fibers increasing satiety. For example, a study from the Catholic University of Louvain, France, included 10 healthy adults who were given 16 grams of prebiotic per day or a placebo for two weeks. The subjects were tested for hydrogen excretion through the breath as well as plasma glucagon-like peptides. These measurements confirmed the subjects’ feelings of satiety after meals9.

An extensive review of multiple studies from the University of Calgary found that fermentable prebiotic fibers promote the gut’s probiotics, and this correlated with increases in satiety hormones10. Another review involving the University of Reading’s Dr. Gibson had similar findings11.

Mr. Varde offered results from Roquette’s research. “We’ve conducted a few studies on satiety and weight management. What we’ve found is that 8 grams per day of Nutriose imparts a feeling of satiety in adults.” These results have also been dose-dependent. “With increasing Nutriose consumption, the subjects take in fewer calories. At a level of 14 grams a day, the satiety is enough to have a statistically significant effect on weight management.”

Tom Jorgens, president of Crookston, MN-based PolyCell Technologies, clarified the satiety mechanisms of beta-D-glucans fiber. “Research from the Imperial College in London and University of Naples has found that short chain fatty acids created by fermentation activate endothelial cells in the colon to release satiety hormones such as PYY, GLP-1, GIP. These travel to the brain’s satiety centers and dampen further eating. They also decrease hunger hormones such as ghrelin.”

Research using PolyCell’s barley extract has been consistent with this mechanism. “Subjects consuming beta-glucan soluble fiber from barley in muffins lost an average of two pounds a month, while the control group consuming wheat bran muffins gained an average of two pounds per month in a University of Minnesota clinical trial with 60 subjects,” Mr. Jorgens explained.

Glycemic effects appear to be involved as well. “Overweight adult women showed a significant reduction in peak blood-sugar levels when consuming two grams of barley beta-glucan in a USDA trial. Weight loss and satiety were closely associated with longer glycemic cycles,” Mr. Jorgens added.

Gum Fibers & Dysphagia

Millions of Americans suffer difficulty swallowing both liquids and solids. For these, the importance of functional, fermentable fiber is critical.

TIC Gums’ Mr. Nicolls said that choking can occur from swallowing the thinnest of liquids, like water. Of those, more have trouble swallowing liquids than solids. “Until the middle of the last decade, the most common approach to thicken liquids and pureed foods was to provide agglomerated starch in packets or spoonable containers. However, those same powders may contribute to trouble swallowing.”

TIC Gums supplies an array of conventional and organic gum fibers, such as guar, carrageenan, pectin, locust bean gum, tara gum, acacia and agar using a multitude of different gum systems.

“One common approach to aiding consumption of beverages and foods is thickening them with starch and/or gums. Starch, gums and gums systems, known as hydrocolloids, can add viscosity to liquids and foods, stimulating saliva production and enabling better swallowing,” Mr. Nicolls added.

Inulin: Functional Fermentable

Inulin is a functional fermentable fiber and the subject of significant research. “Inulin helps promote digestive health by stimulating the normal, beneficial bacteria in the digestive tract. Studies have shown that 5 grams of inulin per day help to maintain a healthy digestive tract due to its prebiotic properties,” said Cargill’s Ms. Stauffer.

Cargill’s inulin ingredient, Oliggo-Fiber, is produced from chicory root, one of the best natural sources of inulin. “Chicory fiber promotes the growth of beneficial microflora in the digestive system helping to maintain natural balance,” explained Ms. Stauffer.

This fermentable also has glycemic benefits. “Inulin does not significantly impact blood-sugar levels and is suitable for use in a low glycemic diet,” Ms. Stauffer added.

Fermented Flax

Flaxseed is a quintessential fiber, and its success is related to its fermentability and excellent phytonutrient content. “It’s an important emerging food ingredient due to its rich content of omega 3 alpha linolenic fatty acids (ALA), lignans and fiber,” said Marilyn Stieve of leading flax fiber supplier Glanbia Nutritionals, Fitchburg, WI. “The EFAs (essential fatty acids) contribute to cardiovascular health.”

Glanbia Nutritionals has partnered with The Flax Council of Canada to provide an extensive, updated Flax Research Database for Human Health and Nutrition.

“A unique property of flaxseed is that it contains a gum matrix, known as gum mucilage,” said Ms. Stieve. “Using specially developed processing systems, functional flaxseed products have now been developed that exploit this inherent property.” Glanbia’s flaxseed-based fiber can serve as a functional guar gum replacer.

Rice Hulls: Waste Stream to Prebiotic

Ontario, Canada-based SunOpta Ingredients recently launched a gluten-free fermentable fiber made from rice hulls—normally considered a waste product.

“Being able to use plant material that would normally become part of a waste stream is a sustainable practice,” said Laura Cooper of the SunOpta Ingredients Group. “Rice hulls are very high in silica so SunOpta developed a proprietary hydrothermal process to reduce the silica and produce a soft, flexible fiber. Rice fiber is gluten-free, greater than 90% fiber and is consumer friendly in an ingredient statement. This product is self-affirmed GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe).”

Beta-Glucans

The polysaccharide (1,3)(1,4)-beta-D-glucans molecule resides in cell walls throughout the bran and endosperm of barley, oats, and to a lesser degree, some wheats. In 2002, FDA announced that beta-D-glucans soluble fiber provides cardiovascular benefits12. One of the key mechanisms cited was beta-D-glucans’ ability to inhibit bile acid absorption.

Raw oats and barley range 3-7% beta-D-glucans content, and some barley varieties can be as high as 12%. PolyCell Technologies has developed a barley-based concentrate of beta-D-glucans—marketed by partner SunOpta—averaging 28% beta-D-glucans.

“Our product is known for heart healthy cholesterol reduction, and has a very low Glycemic Index that decreases blood sugar peaks and extends glycemic cycles,” said PolyCell’s Mr. Jorgens.

“The research shows barley beta-glucan forms a viscous matrix that traps some of the cholesterol, bile acids, fats and excess sugars found in the small intestine. As the beta-glucans are fermented in the colon, most of the entrapped materials are on path to exit the body,” he explained.

Fermentable Ayurveda

The ancient science of Ayurveda has utilized fermentables for many centuries through famous digestive formulations such as triphala and chyawanprash.

Amla is common to both formulations. “Amla fruits are rich in fiber content, contributing to the digestive benefits of triphala,” noted Dr. Anurag Pande, vice president of scientific affairs, Sabinsa Corporation, East Windsor, NJ. “Though amla fruit is well known for its antioxidant and other health protective benefits, our amla fiber product concentrates amla’s fiber benefits. Amla’s insoluble fibers help absorb water and create bulk, helping conditions such as constipation.”

Fenugreek seed is another traditional Ayurvedic remedy. “Fenugreek seeds are well known for their anti-diabetic benefits,” said Dr. Pande. “The fiber fraction of fenugreek seeds consists of galactomannans—made up of galactose and mannose units.” Sabinsa’s Fenufiber is an enriched fraction from fenugreek seeds.

A University of Georgia study found fenugreek seed fiber reduced bloating and other gastrointestinal disturbances13. “The results were due to fermentation by GI microflora,” explained Dr. Pande. This study also proved psyllium husk and wheat bran to be fermentables.

Innovative Fermentables

Customers are beginning to see a need for functional, fermentable fibers. “Novel prebiotic fibers are gaining popularity among consumers because there is broader understanding of how the good bacteria in our guts help to support a healthy digestive and immune system,” said Ingredion’s Mr. Luchinger.

Ingredion’s flagship fiber ingredient is Nutraflora, an scFOS, natural prebiotic fiber. “NutraFlora is derived from non-GMO beet or cane sugar using a patented process and a traditional natural fermentation method,” Mr. Luchinger noted.

Roquette also provides several functional, fermentable fibers. “Our hallmark product in the Nutriose line is made from non-GMO corn or wheat,” said the company’s Mr. Varde. “It is 85% fiber, sugar-free and invisible—having no taste or sweetness. It dissolves rapidly in water and imparts almost negligible viscosity in liquids.”

Along with other blended fibers, North Tonawanda, NY-based International Fiber Corp. (IFC) offers a blended cellulose and inner pea fiber. “This fiber blend provides a water holding capacity of three to nine times its own weight,” said IFC’s R&D project leader Fon V. Tuntivanich, PhD. “In addition to binding water through hydrogen bonding, this fiber can also bind additional amounts of water through capillary action.”

Fiber intolerance can be an issue when building fiber intake. “One of the most interesting attributes of Nutriose is its high dietary tolerance. Our clinical studies show that 45 grams/day of Nutriose can be consumed without any major side effects,” Mr. Varde noted.

Research led by Bruce Hamaker, PhD, a food science professor at Purdue University, has resulted in a new fermentable: a natural corn-derived product entrapped in alginate. Dr. Hamaker and Dr. Ali Keshavarzian from the Rush University Medical Center have determined through their research that the alginate microbeads slowly ferment as they reach the lower intestines.

The Purdue research evolved from a quest to find a more tolerable prebiotic fiber. “Intolerance to most prebiotic fiber is primarily produced from rapid fermentation. This takes place as our gut’s bacteria extract energy from the fiber. Depending upon the quantity and how quickly it ferments, practically everyone is affected by some fiber intolerance,” explained Dr. Hamaker.

Nutrabiotix’ Dr. Cisneros described the patent-pending fermentable’s intestinal efficacy. “Tolerability allows for increased dietary fiber ingestion and targeted action to the entire colon. This increases the good bacteria in the large intestine. As these bacteria use the fiber as their energy source, they produce fermentation products that decrease inflammation and provide a healthy large intestine environment.”

According to Dr. Cisneros, the new fiber ingredient affects the “far reaches of the distal colon where our diets tend to produce a region devoid of nutrients.”

Integrating Fermentables

Incorporating these effects into foods and beverages is made easier by this wave of new functional fermentables. “Consumers are expecting more healthful paybacks from the foods they already consume regularly,” noted TIC Gum’s Mr. Nicoll.

Fiber content is only one dimension of functional fibers. “Consumers are looking for benefits beyond just fiber. Inulin-based fiber is different from many traditional soluble fibers. It has unique, important health and functional benefits. Breads and other baked goods, ice cream, bars, beverages and many other product applications have been used with it,” said Cargill’s Ms. Stauffer.

IFC’s Dr. Tuntivanich sees functional, fermentable fibers as important considerations for childhood diet and obesity problems. “The U.S. national school lunch and breakfast programs have new objectives to reduce the level of saturated fat in meals in order to supply students with appropriate calorie levels. Fiber can be used to replace some meat ingredients originally contributing to saturated fat while maintaining good taste.”

The new functional fibers are versatile. “We have customers using our product in nutritional beverages—in both RTD (ready-to-drink) and dry mixes—supplement powders, weight loss powders and tablets and capsules,” said Ingredion’s Mr. Luchsinger. “Because Nutraflora remains stable in many processing conditions such as pasteurization, batch cooking, retorting, baking, extrusion, shear drying and so on, there are many different ingredient uses such as retail smoothies, gummy and confection applications, cold cereal and nutritional bar products and yogurt and dairy-based beverages.”

The newest gums also blend well with beverages. “Ticaloid products hydrate rapidly and disperse easily,” said Mr. Nicoll. “Also important is the minimal impact these gums and gum systems have on flavor.”

Flaxseed’s gums also provide functional blending capability, according to Glanbia’s Ms. Stieve. “Flax ingredient solutions with strong water-binding capabilities and gum mucilage can be used to replace gum systems in food applications such as gluten-free baked goods, where it can improve both texture and shelf life in gluten-free tortillas, sheeted doughs, batters, breadings, sweet baked goods and fresh breads. Gums or hydrocolloid systems that help manage moisture content are essential for gluten-free baked goods, since the flours that can be used tend to dry out food formulations.”

Dr. Tuntivanich noted that some fibers can be blended with dried ingredients before use. “In some special cases, fibers may need to be hydrated before use. The benefit of using IFC fibers is that fibers can absorb the aqueous phase almost instantly, therefore, reducing the overall production time. Fibers also help to retain moisture or reduce water loss from a product; thus providing a superior, less oily texture.”

Functional fiber can also help increase shelf life, he added. “These fibers bind both water and fat, therefore stabilizing the product structure and reducing water and fat loss during cooking. Special fiber blends can help to stabilize deterioration of product texture due to cryogenic damage and fluctuating temperature storage.”

“Rice fiber can be used to increase the fiber content of baked goods, snacks and nutrition bars,” added SunOpta’s Ms. Cooper.

Nutrabiotix’ new fiber product from Purdue also has numerous applications. “We’ve designed the product to be used in several different types of formulations,” explained Dr. Cisneros. “We have used encapsulated products in our clinical studies. We’ve done preliminary formulation testing in bars and in yogurts; and other formulations such as cereals, dairy products and a host of other foods and beverages are possible.”

Researchers and ingredient suppliers are now working together to utilize the science to feed our probiotics. The University of Reading’s Dr. Gibson discussed future research in this area. “Our ongoing studies will involve metabonomics, whereby biological fluids can be subject to NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance) profiling to determine all the metabolites present.”

Dr. Gibson underscored the seriousness of the prebiotic mission with respect to global health. “As gastrointestinal disorders are prevalent worldwide, prebiotics can provide an important role in the prophylactic management of various acute and chronic gut-derived conditions.”

About the author: Case Adams is a California Naturopath and holds a PhD in Natural Health Sciences. He has written 20 books on natural health, including two books on probiotics. He can be contacted at case@caseadams.com.

References

1. Maki KC, Gibson GR, Dickmann RS, Kendall CW, Oliver Chen CY, Costabile A,

Comelli EM, McKay DL, Almeida NG, Jenkins D, Zello GA, Blumberg JB. Digestive and physiologic effects of a wheat bran extract, arabino-xylan-oligosaccharide, in breakfast cereal. Nutrition. 2012 Jul 6.

2. Walton GE, Lu C, Trogh I, Arnaut F, Gibson GR. A randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled cross-over study to determine the gastrointestinal effects of consumption of arabinoxylanoligosaccharides enriched bread in healthy volunteers. Nutr J. 2012 Jun 1;11(1):36.

3. A Report of the Panel on Macronutrients, Subcommittees on Upper Reference Levels of Nutrients and Interpretation and Uses of Dietary Reference Intakes, Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes. "7 Dietary, Functional, and Total Fiber." Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2005.

4. Anderson JW, Baird P, Davis RH Jr, Ferreri S, Knudtson M, Koraym A, Waters V, Williams CL. Health benefits of dietary fiber. Nutr Rev. 2009 Apr;67(4):188-205; Lattimer JM, Haub MD. Effects of dietary fiber and its components on metabolic health. Nutrients. 2010 Dec;2(12):1266-89; Roberfroid M, Gibson GR, Hoyles L, McCartney AL, Rastall R, Rowland I, Wolvers D, Watzl B, Szajewska H, Stahl B, Guarner F, Respondek F, Whelan K, Coxam V, Davicco MJ, Léotoing L, Wittrant Y, Delzenne NM, Cani PD, Neyrinck AM, Meheust A. Prebiotic effects: metabolic and health benefits. Br J Nutr. 2010 Aug;104 Suppl 2:S1-63.

5. Theuwissen E, Mensink RP. Water-soluble dietary fibers and cardiovascular disease. Physiol Behav. 2008 May 23;94(2):285-92.

6. Karalus M, Clark M, Greaves KA, Thomas W, Vickers Z, Kuyama M, Slavin J. Fermentable fibers do not affect satiety or food intake by women who do not practice restrained eating. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 Sep;112(9):1356-62.

7. Hess JR, Birkett AM, Thomas W, Slavin JL. Effects of short-chain fructooligosaccharides on satiety responses in healthy men and women. Appetite. 2011 Feb;56(1):128-34. Epub 2010 Dec 10.

8. Peters HP, Boers HM, Haddeman E, Melnikov SM, Qvyjt F. No effect of added beta-glucan or of fructooligosaccharide on appetite or energy intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Jan;89(1):58-63.

9. Cani PD, Lecourt E, Dewulf EM, Sohet FM, Pachikian BD, Naslain D, De Backer F, Neyrinck AM, Delzenne NM. Gut microbiota fermentation of prebiotics increases satietogenic and incretin gut peptide production with consequences for appetite sensation and glucose response after a meal. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Nov;90(5):1236-43.

10. Parnell JA, Reimer RA. Prebiotic fiber modulation of the gut microbiota improves risk factors for obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Gut Microbes. 2012 Jan-Feb;3(1):29-34.

11. Brownawell AM, Caers W, Gibson GR, Kendall CW, Lewis KD, Ringel Y, Slavin JL. Prebiotics and the health benefits of fiber: current regulatory status, future research, and goals. J. Nutr. 2012 May; 142(5):962-74.

12. Food and Drug Administration, HHS. Food labeling: health claims; soluble dietary fiber from certain foods and coronary heart disease. Interim final rule. Fed Regist. 2002 Oct 2;67(191):61773-83.

13. Al-Khaldi SF, Martin SA, Prakash L. Fermentation of fenugreek fiber, psyllium husk, and wheat bran by Bacteroides ovatus V975. Curr Microbiol. 1999 Oct;39(4):231-2.