FDA Leadership Discuss Rationale for Reorganization, Hope for Better Collaboration and Agility

By By Mike Montemarano, Associate Editor | 02.01.24

Agency’s top brass relayed its intentions about the agency’s largest reorganization including internal operations and effects on regulated industries.

The planned reorganization of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), one of the most important developments for nutraceutical industry stakeholders, will be the largest structural change the agency has ever gone through.

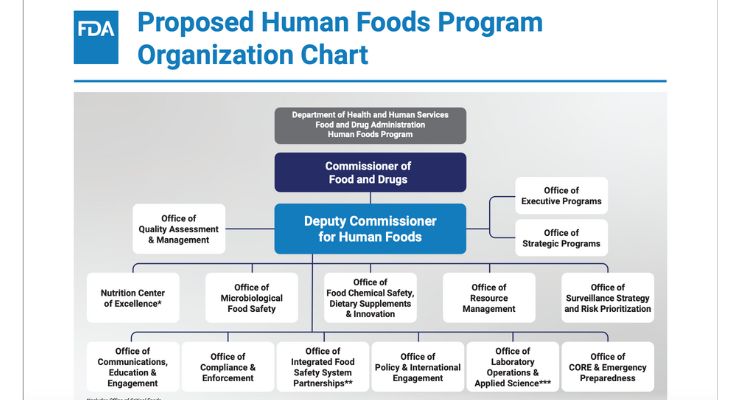

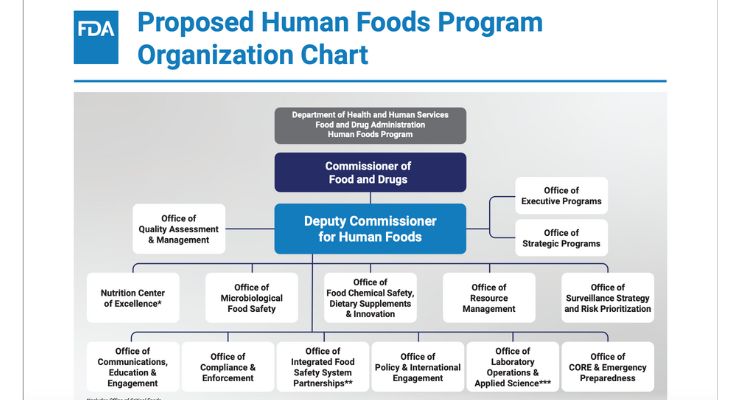

The agency’s unification of its Human Foods Program involves combining the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) and the Office of Food Policy and Response (OFPR) and certain functions of the Office of Regulatory Affairs (ORA) under one leader, and comes with many moving parts and changing titles.

Key updates include the appointment of Jim Jones as deputy commissioner of the newly-created Human Foods Program (HFP), along with a larger executive team in HFP, and new intra-HFP offices, such as the Center for Excellence in Nutrition; an Office of Integrated Food Safety System Partnerships; a Human Foods Advisory Committee; and more.

Further, the Office of Regulatory Affairs’ restructuring is intended to reduce redundancies in FDA’s field activities, essentially by having more inspectional personnel under one roof, centralizing inspection data, and creating other kinds of operational efficiencies.

“Because the review process for government agency reorganizations is very long, we needed to submit a proposal very early on in the process,” said Janet Woodcock, principal deputy commissioner at FDA during a webinar on Jan. 19 hosted by the Alliance for a Stronger FDA. “Because our mission is continually broadening, we need to be able to meet that mission as much as our resources allow … This started out as a food-driven reorganization, but became much bigger.” Woodcock plans to retire from the agency early this year, capping nearly four decades of service at FDA.

Most units within the FDA will be impacted, which will in turn affect many functions, Woodcock noted. That’s because the Reagan-Udall Foundation’s evaluation of the agency found that issues related to how different FDA offices interacted weren’t limited to the field of food products.

FDA has officially submitted its finalized proposal to the Department of Health and Human Services for an external review, which is the third and final major phase of enacting the reorganization.

As part of expediting the reorganization, the entire plan is budget-neutral, Woodcock noted.

One of the biggest inefficiencies she hopes will come of the restructuring is more clarity and promptness in overall enforcement action.

“This is something that appeals to everyone, as when you have a 483 [a notification from the agency to a company about potential violations of the law] you want to know as soon as possible what’s going to happen, and have people who can deal with you very effectively to get out of that situation. And we all want products to be made safely. We’re consolidating a lot of things, like consumer complaints, our own communication efforts, and intake of defects, adverse events, and more, all going to one place. It’s our hope that we get a tracking system for all these things that won’t cost a lot of money.”

He expects to see major improvements in a number of risk management tools, including partnerships with states, and activities related to compliance, policy, communications, applied research, and outbreak response.

Jones said the HFP’s three core priorities will be: managing public risk through nutrition, microbiological food safety, and chemical safety. Surveillance activities will reflect these three core concepts. “With our limited resources, we’re trying to focus on where risks are the highest,” Jones said.

With many of the Office of Regulatory Affairs’ functions moving under the HFP’s umbrella, firms that are being inspected will have one office, rather than two, to contact about inspection and enforcement actions, Jones said.

“As agencies have grown over time, what might have made sense before we had internet and instant communication doesn’t anymore—people don’t need to be in physical spaces as often,” he noted. “We’re cutting off unnecessary transfers of information, and there will be fewer instances of people passing off the baton and running into disagreements or confusion.”

“With a new inspection platform, we’re hoping that everyone can be online, and see pictures and more information from wherever they are,” Woodcock added, “and more easily identify which parties need to be part of any given inspection decision.”

“That realignment will eliminate a lot of duplication, and bring investigators closer to the Human Foods Program staff when the agency needs to evaluate ongoing inspections,” said Michael Rogers, associate commissioner of regulatory affairs at FDA.

With HFP taking on more consumer complaint responsibilities, OII will have more resources available to do high-priority field evaluations upon HFP’s request, Rogers said, which will ensure that all serious complaints make it to appropriate senior leadership faster.

Within OII, two new offices will be created: the Office of Field Operations, which will “provide support for organizational quality efforts”; and the Office of Emergency Response, which will coordinate the agency’s response to emergencies and natural disasters for all regulated products and FDA-regulated facilities. While most inspectional activity will be impacted in some way by the restructuring, how criminal investigations are conducted will remain unchanged.

“Many cases and programs within the Office of Regulatory Affairs didn’t have a direct reference authority,” Rogers said. “We’re standardizing our approach and getting faster classification of all inspections. This will create new contacts for the regulated industry, including the people who need to be contacted for corrective actions, but we’ll make sure that information gets out there in order to make the transition as seamless as possible.”

“The OCS will have an expansive network of labs for scientific and analytical support for the entire agency,” Bumpus said. Further, by merging FDA’s Office of Counterterrorism and Emerging Threats with a newly created Office of Regulatory and Emerging Science, all under the OCS, FDA’s overall regulatory science and preparedness efforts will be stronger, she said.

The agency’s unification of its Human Foods Program involves combining the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) and the Office of Food Policy and Response (OFPR) and certain functions of the Office of Regulatory Affairs (ORA) under one leader, and comes with many moving parts and changing titles.

Key updates include the appointment of Jim Jones as deputy commissioner of the newly-created Human Foods Program (HFP), along with a larger executive team in HFP, and new intra-HFP offices, such as the Center for Excellence in Nutrition; an Office of Integrated Food Safety System Partnerships; a Human Foods Advisory Committee; and more.

Further, the Office of Regulatory Affairs’ restructuring is intended to reduce redundancies in FDA’s field activities, essentially by having more inspectional personnel under one roof, centralizing inspection data, and creating other kinds of operational efficiencies.

Where the Reorg Stands

The reorganization effort, which began with an evaluation of the Human Foods Program in 2022, is expected to come to a close in 2024.“Because the review process for government agency reorganizations is very long, we needed to submit a proposal very early on in the process,” said Janet Woodcock, principal deputy commissioner at FDA during a webinar on Jan. 19 hosted by the Alliance for a Stronger FDA. “Because our mission is continually broadening, we need to be able to meet that mission as much as our resources allow … This started out as a food-driven reorganization, but became much bigger.” Woodcock plans to retire from the agency early this year, capping nearly four decades of service at FDA.

Most units within the FDA will be impacted, which will in turn affect many functions, Woodcock noted. That’s because the Reagan-Udall Foundation’s evaluation of the agency found that issues related to how different FDA offices interacted weren’t limited to the field of food products.

FDA has officially submitted its finalized proposal to the Department of Health and Human Services for an external review, which is the third and final major phase of enacting the reorganization.

As part of expediting the reorganization, the entire plan is budget-neutral, Woodcock noted.

One of the biggest inefficiencies she hopes will come of the restructuring is more clarity and promptness in overall enforcement action.

“This is something that appeals to everyone, as when you have a 483 [a notification from the agency to a company about potential violations of the law] you want to know as soon as possible what’s going to happen, and have people who can deal with you very effectively to get out of that situation. And we all want products to be made safely. We’re consolidating a lot of things, like consumer complaints, our own communication efforts, and intake of defects, adverse events, and more, all going to one place. It’s our hope that we get a tracking system for all these things that won’t cost a lot of money.”

The New Human Foods Program

Jones, who will lead the newly-created Human Foods Program, which will include a new Office of Food Chemical Safety, Dietary Supplements, and Innovation), said that merging all of FDA’s human food functions which are programmatic rather than investigational in nature will help the agency be more clear about its priorities.He expects to see major improvements in a number of risk management tools, including partnerships with states, and activities related to compliance, policy, communications, applied research, and outbreak response.

Further Reading: ODSP Director Highlights Agency Priorities Amid Proposed Reorganization

Jones said the HFP’s three core priorities will be: managing public risk through nutrition, microbiological food safety, and chemical safety. Surveillance activities will reflect these three core concepts. “With our limited resources, we’re trying to focus on where risks are the highest,” Jones said.

With many of the Office of Regulatory Affairs’ functions moving under the HFP’s umbrella, firms that are being inspected will have one office, rather than two, to contact about inspection and enforcement actions, Jones said.

“As agencies have grown over time, what might have made sense before we had internet and instant communication doesn’t anymore—people don’t need to be in physical spaces as often,” he noted. “We’re cutting off unnecessary transfers of information, and there will be fewer instances of people passing off the baton and running into disagreements or confusion.”

“With a new inspection platform, we’re hoping that everyone can be online, and see pictures and more information from wherever they are,” Woodcock added, “and more easily identify which parties need to be part of any given inspection decision.”

Office of Inspections and Investigations

What is now the Office of Regulatory Affairs (ORA) will, in effect, become the Office of Inspections and Investigations (OII), as more of the programmatic responsibilities transition over to the HFP.“That realignment will eliminate a lot of duplication, and bring investigators closer to the Human Foods Program staff when the agency needs to evaluate ongoing inspections,” said Michael Rogers, associate commissioner of regulatory affairs at FDA.

With HFP taking on more consumer complaint responsibilities, OII will have more resources available to do high-priority field evaluations upon HFP’s request, Rogers said, which will ensure that all serious complaints make it to appropriate senior leadership faster.

Within OII, two new offices will be created: the Office of Field Operations, which will “provide support for organizational quality efforts”; and the Office of Emergency Response, which will coordinate the agency’s response to emergencies and natural disasters for all regulated products and FDA-regulated facilities. While most inspectional activity will be impacted in some way by the restructuring, how criminal investigations are conducted will remain unchanged.

“Many cases and programs within the Office of Regulatory Affairs didn’t have a direct reference authority,” Rogers said. “We’re standardizing our approach and getting faster classification of all inspections. This will create new contacts for the regulated industry, including the people who need to be contacted for corrective actions, but we’ll make sure that information gets out there in order to make the transition as seamless as possible.”

More Scientists Under One Roof

With the creation of the Office of the Chief Scientist (OCS), FDA anticipates that its researchers will have increased opportunities for collaboration, and a more centralized information management system, noted Namandjé Bumpus, PhD, chief scientist at FDA.“The OCS will have an expansive network of labs for scientific and analytical support for the entire agency,” Bumpus said. Further, by merging FDA’s Office of Counterterrorism and Emerging Threats with a newly created Office of Regulatory and Emerging Science, all under the OCS, FDA’s overall regulatory science and preparedness efforts will be stronger, she said.