In prior Business Insights columns we have offered insight on claims made for nutritional products, scientific support for product claims, and regulatory considerations for both the U.S. and internationally. In this column, Dave Wilson joins Greg Stephens to explore additional questions around evidence of clinical benefit for “nutraceuticals,” a term we use to include dietary supplements, functional foods, and vitamin and nutritional products.

What clinical evidence is required of nutraceuticals? What evidence exists? What conclusions can be made? And what are some needs and opportunities for evidence generation in nutraceuticals? In the U.S., evidence requirements for nutraceuticals include evaluation of safety for ingredients, which are required to be listed on the label. It is optional to make claims of clinical benefit to bring a nutraceutical to market.

Claims of clinical benefit for nutraceuticals can be expressed in terms of structure/function. These claims define how the compound affects the structure or function of the human body. Companies cannot make claims that nutraceutical products “diagnose, mitigate, treat, cure, or prevent a specific disease or class of disease,” according to FDA regulations (21 USCA 343). If the company desires to do so, it has two options: 1) it can bring the product to market as a drug following drug approval regulations, or 2) it can petition the FDA for a Health Claim and show significant scientific agreement (SSA) among qualified experts that the claim is supported by the totality of publicly available scientific evidence.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has primary responsibility for claims on product labeling, including packaging, inserts, and other promotional materials distributed at the point of sale.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has primary responsibility for claims in advertising, including print and broadcast ads, infomercials, catalogs, and similar direct marketing materials. The essence of FTC guidance on dietary supplement advertising is truth in advertising: “truth-in-advertising law can be boiled down to two common-sense propositions: 1) advertising must be truthful and not misleading, and 2) before disseminating an ad, advertisers must have adequate substantiation for all objective product claims.”

Claim substantiation by the FTC is generally viewed as flexible and does not specify quality, quantity, or methodology. FTC guidance calls for a “reasonable basis” for expressed and implied claims. Also, evaluation is “sufficiently flexible” to ensure consumers have access to products, and at the same time be “sufficiently rigorous” so consumers can have confidence in the “accuracy” of the information. What is reasonable, sufficient, or high enough accuracy for confidence is not defined. Not only is this guidance flexible, but it is also lax.

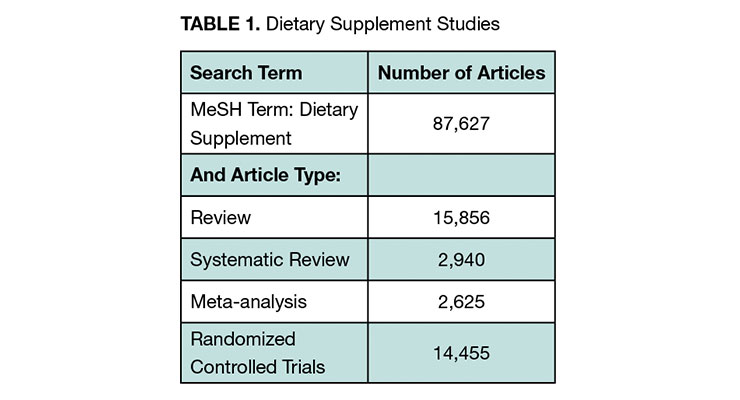

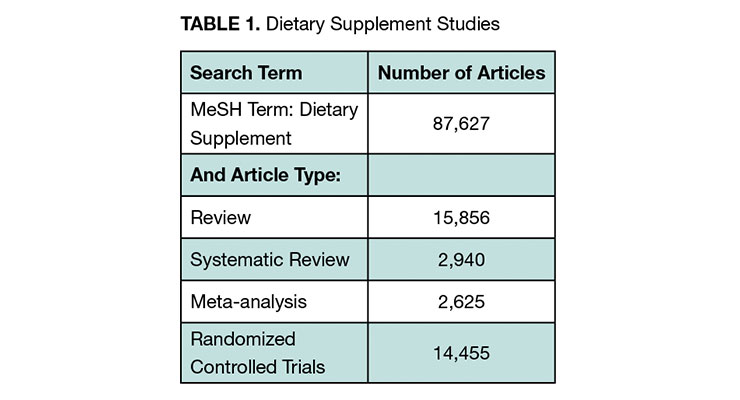

We sought to cast a wide net in exploring what evidence of clinical benefit for nutraceuticals exists. We included expert opinion, literature review, and clinical study registry information. A targeted literature review was conducted with the search engine PubMed. We searched “dietary supplement” as a medical subject heading (MeSH term). The body of evidence is quite substantial with more than 87,000 published dietary supplement publications and over 14,000 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (See Table 1). RCTs are the “gold standard” for proof of clinical benefit. They are required for drug approval by all the leading regulators globally. Meta-analyses combine data from studies into a single analysis for more statistical power.

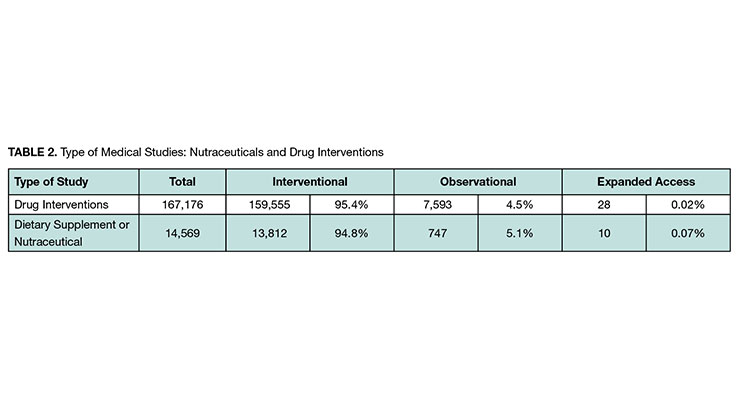

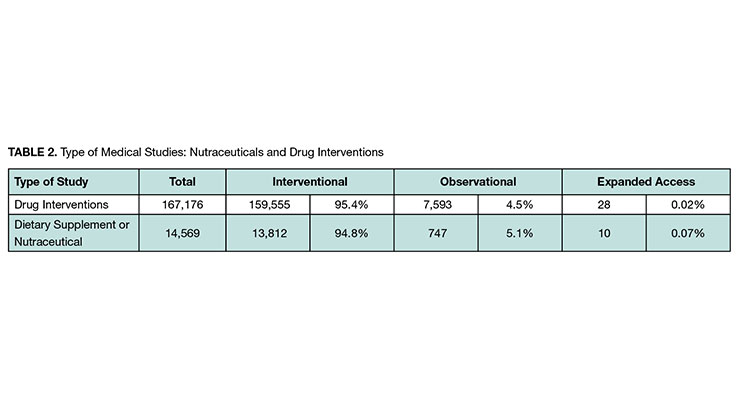

Information on clinical studies was gathered on completed and ongoing studies from ClinicalTrials.gov, a registry database of more than 390,000 medical studies conducted in about 220 countries. The database includes information on both completed and ongoing clinical studies. For the search, we entered the term “Dietary Supplement OR Nutraceutical” in the “Intervention” field. We also provide some comparisons to “Drug Interventions” searched in the same field.

We found more than 14,000 nutraceutical studies with a distribution of type of study like that of drug intervention studies (see Table 2). The vast majority in both cases were interventional, which are studies where participants are assigned to alternative interventions (or no intervention).

For nutraceuticals studies, we looked at the number of studies by disease area and by nutraceutical intervention. Table 3 includes the top five in each category.

The proportion of studies sponsored by industry for drug interventions is approximately double that for nutraceuticals (see Table 4). This was expected, given that the clinical study requirements to bring drugs to market is so much greater.

A recent

Washington Post article gathered expert opinion on dietary supplement evidence from the NIH Office of Dietary Supplements, the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, and the Council for Responsible Nutrition. The following question was asked in separate interviews: “Which dietary supplements actually have well established benefits?”

Pulling together the responses, there were a total of eight dietary supplements and five vitamins and minerals that made the list. To put that in context, there are estimates of more than 85,000 supplement products in the U.S. marketplace.

1 The article reached a conclusion reflected in the title: “Most dietary supplements don’t do anything. Why do we spend $35 billion a year on them?”

What can be concluded from clinical evidence is a broad question to which we took a broad and top-level review.

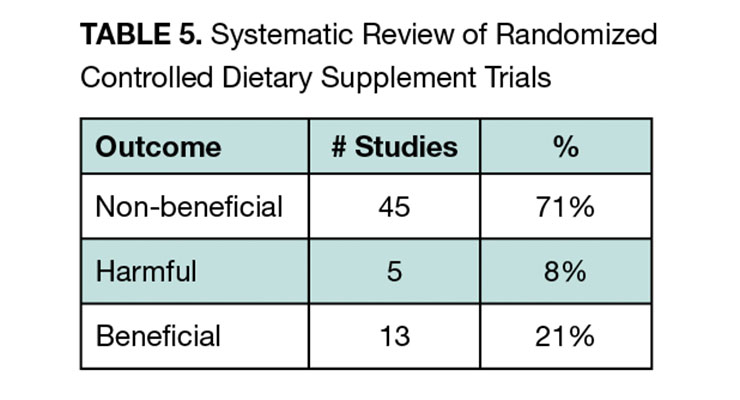

We evaluated systematic reviews of clinical studies of nutraceuticals; we did not conduct one. Our PubMed search (Table 1) generated 2,940 systematic reviews. We used the search term “Dietary Supplement OR Nutraceutical” in the Title or Abstract field, and narrowed that down to 175 citations. We reviewed the titles and abstracts looking for studies that spanned products and conditions. Practically all the systematic reviews focused on a specific disease area, specific product, or a combination. In our review, we only found one study that spanned products and conditions and we report the findings here.

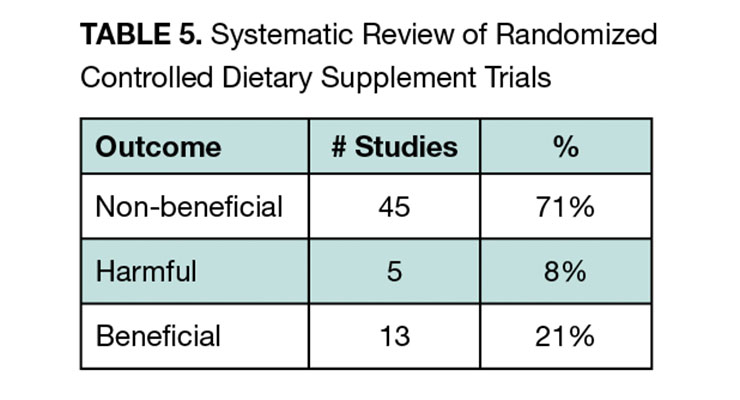

Marik and Flemmer had the broad goal “to systematically review the literature to identify RCTs that investigated clinically relevant outcomes from the use of dietary supplements and then to synthesize and summarize these data.”

2

They focused on RCTs and followed QUORUM group guidelines for systematic review. The broad scope of the study included a search that identified 6,224 studies. Ultimately, 63 studies representing 428,357 patients with a mean duration of 4.7 years qualified for inclusion. To assess benefits across this heterogenous set of studies with varying endpoints, the authors classified the studies in a semiquantitative manner into three categories (non-beneficial, beneficial, harmful) according to whether the endpoint(s) of each study reached statistical significance.

Supplements were found to be non-beneficial in 71% of studies compared to 21% where they were beneficial, and 8% where they were harmful (see Table 5). Beneficial study results came from five supplements including vitamin E, folic acid, vitamin D, omega-3 fatty acids, and selenium. The authors concluded that except for vitamin D, which had beneficial results in six of 13 studies, and omega-3 fatty acids, which had beneficial results in three of five studies, data does not support the widespread use of supplements.

A very small proportion of nutraceutical products have any published evidence of clinical benefit. The evidence that exists is skewed to the lower end of the hierarchy of evidence quality. And from the evidence that exists, a large percentage does not show benefit. In these cases, ultimately a clinically and statistically significant benefit may not exist, or it may but the study was not properly designed or adequately powered to detect it.

The needs and opportunities for generating clinical evidence first depends on perspective. We consider consumers, health professionals, and nutraceutical companies.

A study on consumer preferences and willingness to pay for nutraceuticals provides some insight on the potential value consumers place on evidence. Teoh and colleagues (Value Health Reg Issues, 2021) conducted a discrete choice study with Malaysian consumers and reported that they were willing to pay $100 more for nutraceuticals that had scientific proof of clear effectiveness versus not having that data available.

3

Safety was found to be the most important factor from the 111 participants in the study with an average willingness to pay $221 more for a nutraceutical with scientific proof of no side effect. While this was a robust study, country-specific attribute preferences and willingness to pay have limited generalizability.

Increasingly, people are accessing information on their own to make medical decisions. Surveys have shown that more than one-third of Americans self-diagnose when they encounter a health problem and about 70% of American adults consult the internet for a variety of medical information.

4

Health professionals are a varied group (physicians, dietitians, nurses, pharmacists, and others) with different roles, influence, and patient interactions, but they are all trained in the use of evidence for clinical decision-making and patient communication. Further, clinical evidence is the foundation for treatment guidelines of every disease, which gets combined with experience, observations, reasoning, and patient preferences. CRN’s 2019 consumer survey found 49% of non-users of dietary supplements might consider using them if a doctor recommended them (15% if a health professional other than a doctor did).

From the perspective of the nutraceutical company, are there value propositions and claims of clinical benefit in terms of structure/function that would increase sales through direct influence on consumer choice, or indirectly through health professional recommendations? Considering various types of evidence, study design, and cost, what is the most cost-effective evidence to increase health professional recommendations and consumer purchases?

When nutraceuticals ultimately improve outcomes and quality of life at a lower cost than alternatives, they have a cost-effective advantage and investment in clinical evidence may have a favorable return on investment.

1. Dwyer, J., et al. (2018). Dietary Supplements: Regulatory Challenges and Research Resources. Nutrients. 10, 41

2. Marik, P., et al. (2012). Do Dietary Supplements Have Beneficial Health Effects in Industrialized Nations: What is the Evidence. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. Mar: 36(2): 159-68.

3. Teoh, S., et al. (2021). Consumer Preferences and Willingness to Pay for Nutraceuticals: A Discrete Choice Experiment. Value Health Reg Issues. 24: 167-172

4. Hochberg, I., et al. (2020). Assessment of the Frequency of Online Searches for Symptoms Before Diagnosis: Analysis of Archival Data. J Med Internet Res. Mar; 22(3): e15065.

Greg Stephens, RD, is president of Windrose Partners, a company serving clients in the the dietary supplement, functional food and natural product industries. Formerly vice president of strategic consulting with The Natural Marketing Institute (NMI) and Vice President of Sales and Marketing for Nurture, Inc (OatVantage), he has 25 years of specialized expertise in the nutritional and pharmaceutical industries. His prior experience includes a progressive series of senior management positions with Abbott Nutrition (Ross Products Division of Abbott Laboratories), including development of global nutrition strategies for disease-specific growth platforms and business development for Abbott’s medical foods portfolio. He can be reached at 267-432-2696; E-mail: gregstephens@windrosepartners.com.

David Wilson has over 25 years of experience in the strategic development of evidence for biopharmaceuticals, medical devices, and nutraceuticals. He has held academic and leadership positions in research and strategic planning, in large companies, small start-ups, CROs, and consulting firms. He brings together strategy and generating evidence of value to support marketing, regulatory, reimbursement and market access. He received an MA in Economics from the University of Iowa and is currently an independent consultant focused on evidence strategy and development. (Contact: Dwilson.esd@gmail.com)