Columns

Spotlight on Clinical Research in the COVID-19 Era

Discerning high quality research evidence from speculation and marketing hype is more important in today’s climate.

By: Gregory Stephens

By: Sheila Campbell

When the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) was unanimously passed by Congress in 1994, the industry and healthcare professionals cheered. At that time, dietary supplement labeling was not tightly regulated. For many products, consumers could not verify the contents with a high level of confidence. Truly, some contained contaminants, and some did not contain the promoted ingredient as stated. There were no uniform manufacturing standards governing product safety and purity.

And some products were marketed based solely on their “story.” For example, the ingredient was found in a remote region of the world being used by the indigenous people who lived into their 100s with no evidence of disease. Little or no scientific substantiation was given, or asked for.

A good story is still important. But from our perspective, a robust promotional narrative was often more relevant in certain distribution channels than others. For example, health food stores, multi-level marketing, and some e-commerce sites benefited more from emphasis on the story compared to products distributed in the health practitioner channel. Practitioners and their patients were less interested in the marketing and more attuned to clinical research supporting efficacy of claims.

But times are changing. First, DSHEA mandates that manufacturers and distributors of dietary supplements and dietary ingredients ensure that products are not adulterated or misbranded. Firms must evaluate the safety and labeling of their products before marketing to ensure that they meet the requirements of DSHEA. The FDA can and is taking action against companies marketing adulterated or misbranded products.

Second, although it is cliché to point out that today’s consumers are savvy, it is a fact. More often than not, they ask for evidence that a product actually does what marketing claims. Enhancing their knowledge, more consumers are asking their healthcare providers for guidance, and practitioners are incorporating the use of dietary supplements into patient care plans. But healthcare professionals will not make recommendations without data.

Third, the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the world. Global experts call for scientific data from well-designed studies, and world leaders echo the need for scientifically based evidence to direct the fight against the virus. No doubt, this requirement affects the dietary supplement industry operations at every level.

Hierarchy of Evidence

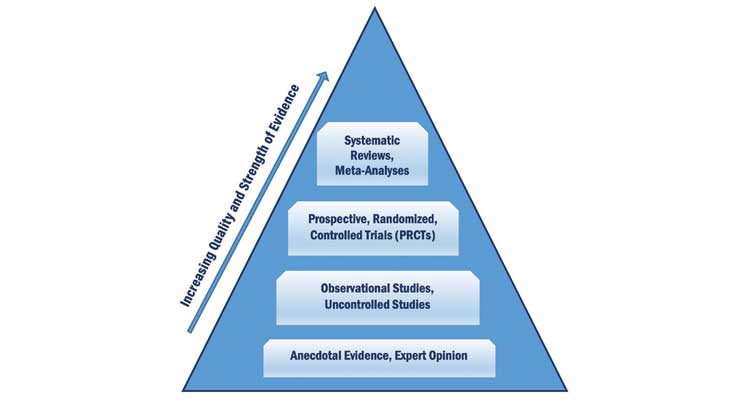

The “gold standard” for claims support is the prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial (PRCT). However, trials of this type may not always be possible, practical, or ethical. Other evidence, including in vitro and animal studies, as well as expert consensus opinion, adds to the evidence that can be used to support claims.

The strongest evidence comes from systematic reviews, meta-analyses and PRCT (see Figure 1). Descriptive, observational reports such as case studies and anecdotal reports provide weaker evidence because their design is not controlled, and data cannot be applied to populations other than the specific one included in the study. Expert opinion provides the weakest support.

FIGURE 1. Hierarchy of Scientific Evidence

Anecdotes and Expert Opinion

Interest in the malaria drug hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for the novel coronavirus provides a timely illustration about the characteristics and merits of various types of scientific evidence gleaned from observations and studies.

Some have claimed hydroxychloroquine improves clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients. In March, French President Emmanuel Macron called for trials of hydroxychloroquine after meeting with researcher Didier Raoult. Anecdotal reports discussed at this meeting raised interest in the drug’s use. The question research needs to answer however, is “Does use of hydroxychloroquine improve clinical outcomes of COVID-19 infection?” Answering the question with only anecdotes offers weak evidence that will not stand alone in today’s environment.

This evidence is not reproducible because the study environment cannot be replicated nor can the data be statistically analyzed. It is also easily falsified. Medical testimony is a little more credible but not much. Expert opinion, say from Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Disease, certainly carries more weight, but still is not equivalent to evidence obtained from a single well-designed and statistically analyzed study.

Observational, Uncontrolled Studies

Observational studies review and record what is happening at a given period. But no conclusions about causation are possible because these studies are not controlled; we do not know what caused the observed effect.

Raoult conducted an uncontrolled study of hydroxychloroquine. He observed and measured changes in viral load and clinical outcome in 80 patients. Scientists complained about this study because Raoult did not include a control group. That is, he did not compare the treatment to anything.

There are a number of study designs that can be used to create theories for further testing or to provide research guidance. Besides observational designs, other study designs include:

- Cross-sectional studies such as surveys

- Case studies can report results from one or more subjects who have been identified with a specific condition. Data are gathered retrospectively for these studies. There are some case study reports about using hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19 infection.

- Data are typically gathered prospectively in a cohort study. Cohort study participants are recruited, then studied over time. These studies often enroll thousands of subjects and may last many years. For example, the study proving the link between smoking and poor health outcomes lasted 50 years.

Prospective, Randomized, Controlled Trials (PRCTs)

PRCTs are considered the gold-standard of study design to show cause and effect. PRCT study design controls bias by randomly assigning subjects to receive the intervention or control treatment; observed outcomes are due to the intervention under study rather than chance. Major PRCTs of hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19 infection have been discontinued because researchers found it caused harm to subjects or offered no beneficial effect.

Systematic Reviews, Meta-Analysis

Systematic reviews are analyses of scientific literature focused on a particular question (e.g., “Does hydroxychloroquine improve outcome in COVID-19 infection?”). The goal of such a review is to identify, appraise, select, and interpret all high-quality research evidence relevant to that question. The operative phrase is “high quality research evidence.”

A meta-analysis uses statistics to combine and analyze data from two or more independent PRCTs. Usually the PRCTs used in a meta-analysis come from the results of a systematic review. As with a systematic review, the validity of the meta-analysis depends on the quality of the studies included in the review on which it is based.

To make sure you are getting the best evidence possible, answer the following questions for each clinical study and report:

- Is the research question clearly and succinctly stated so it applies to your product and desired claims?

- Are appropriate endpoints and their measures clearly and appropriately defined?

- Is the study correctly designed to address the research question and to control for bias?

- Can the study findings be generalized to your population of interest?

- Are the statistical tests appropriate to the study design?

- Are the statistical results adequately analyzed and interpreted, and any potential threats to validity and reliability identified and explained?

- Are the conclusions drawn supported by the data?

Regardless of the indication, well-educated consumers and informed health practitioners provide incentive to conduct appropriately designed studies. To ensure the success of new products, and extend the lifecycle of existing ones, the investment in quality clinical research is a valuable asset.

Gregory Stephens

Windrose Partners

Greg Stephens, RD, is president of Windrose Partners, a company serving clients in the the dietary supplement, functional food and natural product industries. Formerly vice president of strategic consulting with The Natural Marketing Institute (NMI) and Vice President of Sales and Marketing for Nurture, Inc (OatVantage), he has 25 years of specialized expertise in the nutritional and pharmaceutical industries. His prior experience includes a progressive series of senior management positions with Abbott Nutrition (Ross Products Division of Abbott Laboratories), including development of global nutrition strategies for disease-specific growth platforms and business development for Abbott’s medical foods portfolio. He can be reached at 267-432-2696; E-mail: gregstephens@windrosepartners.com.

Sheila Campbell, PhD, RD

Sheila Campbell, PhD, RD, has practiced in the field of clinical nutrition for more than 30 years, including 17 years with Ross Products Division of Abbott Laboratories. She has authored more than 70 publications on scientific, clinical and medical topics and has presented 60 domestic and international lectures on health-related topics. She can be reached at smcampbellphdrd@gmail.com.