Columns

The Effect of Migration on Microbiome & Obesity

The gut microbiome offers an important window into the consequences of diet and lifestyle changes associated with human migration.

By: Dilip Ghosh

Human migration to the West from non-Western nations has been associated with a loss in gut microbiome diversity, which may lead to predisposing individuals to metabolic disease such

as obesity.

Few studies, including a 2018 report, have established that diet and geographical environment are two principal determinants of microbiome structure and function (PNAS, 2010; Nature, 2018).

Substantial biodiversity of microbiota have been found in rural indigenous populations, including novel microbial taxa compared to industrialized populations (Science Advances, 2015; Nature, 2012).

This loss of indigenous microbes or “disappearing microbiota” may be important in explaining the rise of chronic diseases in the modern world (Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2009). Despite the frequent migration of people across national borders, particularly in recent years, the effects of human migration on the human microbiome is little known and to be explored scientifically for tackling growing diseases such as obesity.

Diet & Gut Microbiome

It is well accepted that long-term dietary intake influences the structure-function profile of the trillions of microorganisms residing in the human gut, but it remains unclear how rapidly and reproducibly the human gut microbiome responds to short-term macronutrient change.

Very recently, research from Vangay et al. on the Hmong and Karen people originally from Thailand showed “the short-term consumption of diets composed entirely of animal or plant products alters microbial community structure and overwhelms inter-individual differences in microbial gene expression,” (Cell, 2018).

The animal-based diet increased the abundance of bile-tolerant microorganisms (Alistipes, Bilophila and Bacteroides) and decreased the levels of Firmicutes that metabolize dietary plant polysaccharides (Roseburia, Eubacterium rectale and Ruminococcus bromii). The abundance and activity of Bilophila wadsworthia is increased in the animal-based diet, supporting a link between dietary fat, bile acids, and the outgrowth of microorganisms capable of triggering inflammatory bowel disease. Thus, the gut microbiome offers an important window into the consequences of diet and lifestyle changes associated with human migration.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 10.0px; font: 7.0px ‘Helvetica Neue LT Std’}

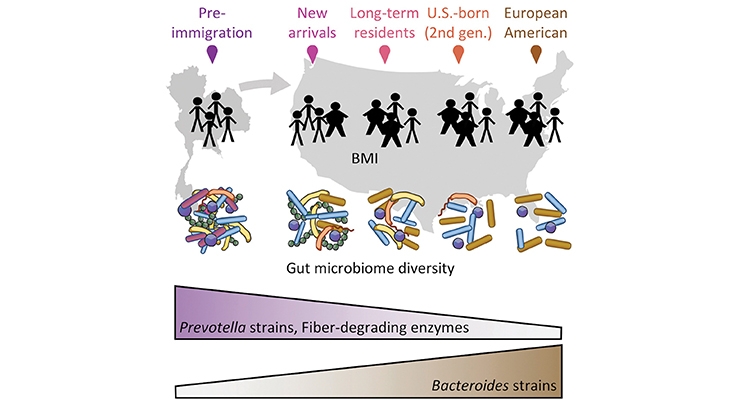

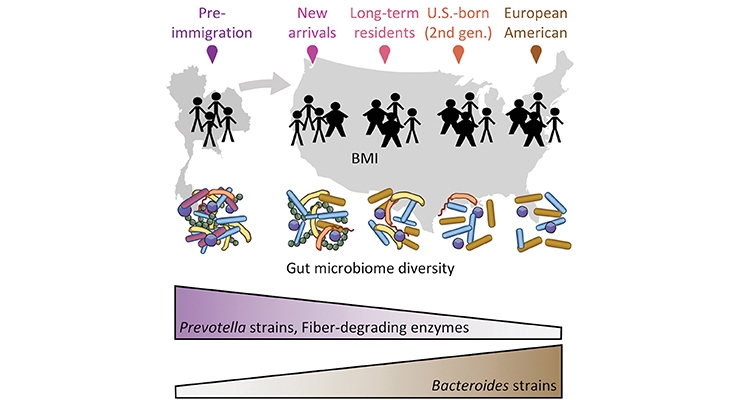

Source: Vangay et al. (Cell, 2018)

The United States: An Ideal Example

The U.S. hosts the largest number of immigrants in the world (49.8 million, or 19% of the world’s total immigrants and approximately 21% of the U.S. population, according to 2017 statistics from the United Nations.

Epidemiological evidence demonstrated that staying in the U.S. increases the risk of obesity and other chronic diseases among immigrants compared with individuals of the same ethnicity that continue to reside in their country of birth.

Both short- and long-term exposure to more westernized diets significantly shift an individual’s microbiome. Metagenome assembly showed that the observed loss of Prevotella strains was associated with loss of carbohydrate-active enzymes dominant in the gut microbiota, including a near-complete loss of certain β-glucanases and other glycoside hydrolases that break down specific dietary fibers.

The study outcome demonstrates that “U.S. immigration is associated with profound perturbations to the gut microbiome, including loss of diversity, loss of native strains, loss of fiber degradation capability, and shifts from Prevotella dominance to Bacteroides dominance.” These changes resulted in obese individuals and continues in second-generation immigrants born in the U.S.

Conclusion

Humans have evolved since the most ancient times along with commensal microbiota. All of the studies on human population groups suggest that microbiota confer benefits on humans. Experts propose that “the disappearance of these ancestral indigenous organisms, which are intimately involved in human physiology, is not entirely beneficial and has consequences that might include post-modern conditions such as obesity and asthma,” (Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2009).

References

- De Filippo C. et al. 2010. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107: 14691-14696.

- Rothschild D. et al. 2018. Environment dominates over host genetics in shaping human gut microbiota. Nature 555: 210–215.

- Clemente J.C. et al. 2015. The microbiome of uncontacted Amerindians. Sci. Adv. 1.

- Yatsunenko T. et al. 2012. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature 486: 222–227.

- Blaser M and Falkow S. 2009. What are the consequences of the disappearing human microbiota? Nature Rev Microbiol., 7: 887–894.

- Vangay P. et al. 2018. US Immigration Westernizes the Human Gut Microbiome. Cell 175: 962–972.

- David L. et al. 2014. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature, 505: 559–563.

Dilip Ghosh, PhD, FACN

nutriConnect

About the author: Dilip Ghosh, PhD, FACN, is director of nutriConnect, based in Sydney, Australia. He is also professionally involved with NICM, Western Sydney University, Australia, and is an Honorary Ambassador with the Global Harmonization Initiative (GHI). Dr. Ghosh received his PhD in biomedical science from University of Calcutta, India. He has been involved in drug development (both synthetic and natural) and functional food research and development both in academic and industry domains. Dr. Ghosh has published more than 90 papers in peer-reviewed journals, and he has authored many books, including: “Biotechnology in Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals,” “Innovation in Healthy and Functional Foods,” “Clinical Perspective of Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals,” and “Pharmaceuticals to Nutraceuticals: A Shift in Disease Prevention under CRC Press. He can be reached at dghosh@optusnet.com.au; www.nutriconnect.com.au.